On 4 March 2021, merely 16 days after a Delhi court’s landmark judgment in M.J. Akbar vs Priya Ramani where the court held that “the right of reputation cannot be protected at the cost of the right of life and dignity of [the] woman”, the Chief Justice of India asked a man accused of raping a minor whether he would marry her. While proposing so, the Chief Justice remarked as to remind the accused that he was a ‘government servant’ and that this was the only way for him to ‘save his job’. The Chief Justice’s comment however shocking is not an anomaly, it is a mere reflection of the understanding of sexual harassment and rape prevalent in our judiciary and society at large.

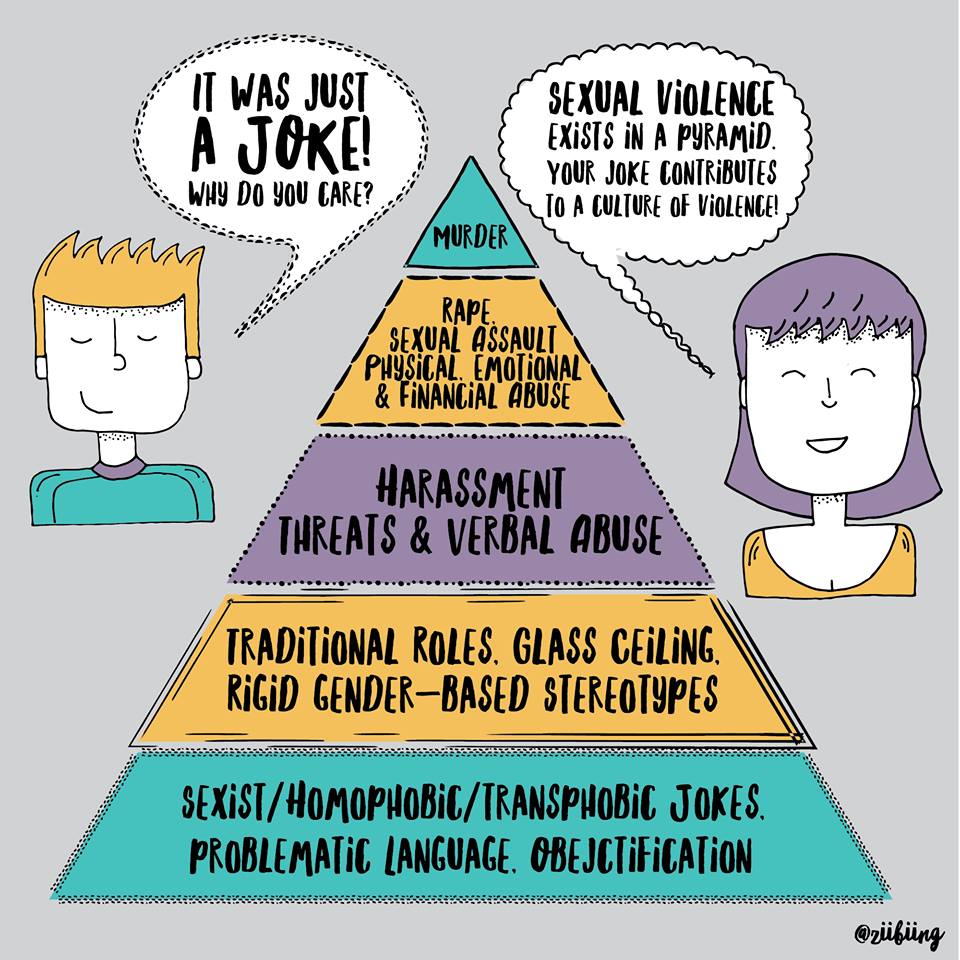

The gravity of patriarchal toxicity prevalent in our society manifests itself in online chart rooms of teenagers such as the ‘bois locker room’ busted by Delhi police in May last year wherein boys as young as 11-13 years of age where commenting on their classmates beginning from casual sexism and escalating to the extent of rape. To the children in this online chat room these conversations were a measure of the sense of humor of their fellow classmates – those who did not participate were considered uptight. Our homes and workplaces are no different. Our family and work chat groups are replete with jokes about women, trans and queer people in bad taste. Any criticism of such jokes is often shrugged off with the argument that jokes are harmless. While in reality, these jokes and the foul language used therein is at the heart of the problem.

Women are often made to feel that they are being too ‘reserved’, that they lack sense of humor and/or are reading too much into things if they voice out their concern against such messages. This creates self doubt and dissuades them from taking any action. On the other hand it perpetuates the idea that heterosexual masculine identity is superior to all and entitled to such behaviour.

It does not come as surprise then that our courtrooms are infested with sexism and mired in cases of sexual misconduct against people holding high offices. In 2013, a law intern reported a case of sexual misconduct against Justice Ashok Ganguly who was then serving as the Chairman of the West Bengal Human Rights Commission after having retired from the Supreme Court. In his reply against a notice served to him by the Supreme Court Justice Ganguly, said that his actions were misconstrued by the young lady, that he had no sexual intentions. No further action was taken in the case.

A similar case was brought against another Justice of the Supreme Court – Swatanter Kumar in 2014. He rubbished all allegations brought against him by his junior and continued to serve as the chairman of the National Green Tribunal.

In 2019, a woman employee of the Supreme Court brought a case against then Chief Justice of India, Ranjan Gogoi alleging that CJI made sexual advances while she was posted for work at his residence office. The CJI not only held the office despite the case, he convened a special bench comprising of himself and two other judges of the Supreme Court to look into the matter which in his words ‘touched upon the independence of judiciary in the country’. In doing so he violated the principle that no one can be a judge in their own case. Subsequently, a committee was formed to look into the matter which concluded the case despite the opposition of the woman and final report of the committee was never made public nor shared with the woman leading to a clean chit to the CJI. All this while the CJI maintained that the woman had a ‘criminal record’ and that the allegations against him were made with the motive to destabilize the judiciary.

A common argument presented in such cases is that the men hold high offices, don a stellar reputation in the society and the case against them is motivated, aimed at defaming them and maligning their great work.

It is in this light that the Priya Ramani judgment becomes even more important and rightly merits celebration.

What does the judgment say?

In 2018, Mobasher Jawed Akbar, the then Minister of State for External Affairs and a well known newspaper editor was accused of sexual harassment by his former colleagues when the #MeToo movement gained momentum in India. One of the persons who called him out was Priya Ramani. Ms. Ramani wrote an article and several twitter posts recounting Akbar’s unwelcome behaviour when she went to interview for a job at the newspaper Asian Age in 1992. M.J. Akbar was then the editor of the newspaper who called her to a hotel room late in the evening for the interview.

Several other women gradually started reported of Akbar’s unwelcome advances and gestures towards themselves while working under him. Eventually, Akbar resigned and filed a criminal defamation suit against Priya Ramani. Such cases are so commonplace today that there is a term for them – SLAPP or strategic lawsuit against public participation. SLAPP cases are filed with the intent to intimidate and silence opponents by burdening them with costs of legal defense.

After a 2-year long trial, court dismissed the complaint against Priya Ramani and found no merit for criminal defamation. While deciding so court heavily relied on the point that M.J. Akbar is not a man of ‘stellar reputation’ as he claims, for several women have called him out for sexual assault. In the judgment the court held that, “ the attack on the character of sex abuser or offender by sex abuse victim, is the reaction of self defence after the mental trauma suffered by the victim regarding the shame attached with the crime committed against her. The woman cannot be punished for raising voice against the sex abuse on the pretext of criminal complaint of defamation as the right of reputation cannot be protected at the cost of the right of life and dignity of woman as guaranteed in Indian Constitution under article 21 and right of equality before law and equal protection of law as guaranteed under article 14 of the Constitution. The woman has a right to put her grievance at any platform of her choice and even after decades”, and that an act of sexual harassment is not limited to physical assault.

In doing so the court has dealt with two arguments commonly used to stifle the complaints of victims – why didn’t they raise their voice at the time of the incident and why did they choose to go public in the social media when there are legal remedies available to them.

However, it must be noted that this was a case of criminal defamation and not sexual harassment in particular. In cases of sexual harassment judgments have watered down the interpretation of law and set dangerous precedents. For instance, in Mahmood Farooqui v. State (GNCT of Delhi) the court held that a feeble ‘No’ can not be held as denial of consent. The High Court overturned a lower court order stating “[…] if it was without the consent of the prosecutrix, whether the appellant could discern/understand the same”. These vague expansions of what is consent and how is it to be understood and obtained is based on the dominant masculine notions of pleasure which lead to cases of sexual violence being eroticised during the trial and used for the advantage of the perpetrator.

Judgment in the Priya Ramani case also makes one ponder whether the court would have reached the same conclusion if Akbar could prove that he was a man of stellar reputation? That his image was being tarnished because of the allegations brought by Priya Ramani? What would have happened if Priya Ramani’s case was an exclusive one and there were no other allegations against M.J. Akbar? And most importantly, why did the court admit the case in the first place when it was clear that M.J. Akbar had moved court to set an example through this case for all other women who had started speaking against his predatory behaviour and silence them. By allowing this trial to continue for 2 years did the court not allow the abuse of judicial process by a powerful man?

It remains to be seen as to whether this judgment will put an end to future SLAPP cases related to sexual harassment where it is clear that the trial is a mere tool to silence the survivor and the process of trial becomes punishment in itself. Meanwhile, a more pressing issue at hand is staring us in the face – there has been a 14% rise in cases of sexual harassment at workplace in India among BSE top 100 companies between 2018-19. This is just the tip of the iceberg cases of sexual harassment are seldom reported. Most reported cases are never followed up and hardly a few reach conclusion. Companies however grandly advertise their ‘zero tolerance’ sexual harassment policies and shower discounts and gifts on International Working Women’s Day.

A Zero Tolerance policy is no Policy

Since the promulgation of Prevention of Sexual Harassment at Workplace Act, 2013 it has become mandatory for employers to constitute an Internal Complaints Committee to create a safe space for women to raise a complaint, organise workshops and awareness programs to sensitise workers. However, employers have done a mere lip service to the cause in the name of complying with the law while parroting the fancy copies written by their public relations agencies. The measures taken by the employers merely pay lip service to the cause at best. While they parrot fancy sounding copies composed by their public relations agencies the real on-ground compliance and long term strategies to create a harassment free environment are missing. For instance—support mechanisms for the survivor within the workplace, the presence of a clear policy regarding the offenders are areas where a clear vision and protocols are mostly absent in the ‘zero tolerance policies’.

Employers prefer this vagueness because it allows them to maneuver their actions on a case to case basis. This approach veils the fact that sexual harassment at workplace is not an individual but systemic problem which affects everyone. An act of sexual harassment does not affect the victim alone, it turns the entire workplace into a hostile workplace for all women, queer and trans people.

Employers allow this hostile environment to exist because individualism, inequality and intimidation are intrinsic to the profit model of capitalist businesses. The power imbalance between men and women at the workplace makes business sense to employers. Management uses this constant threat to exert control over the productivity of workers.

Exercise of power is central to sexual harassment at the workplace and hence majority of incidents occur between women workers and/or employees and their seniors, supervisors or managers. Not only do seniors, supervisors and managers have, by definition, greater authority and power, they also control the conditions of work at the workplace such as assigning tasks, setting work targets, evaluating performance and recommending promotions. While it might be difficult to find any working woman who has not been sexually harassed at work, the incidence of harassment rises as the vulnerability of the woman rises. Thus the incidence of sexual violence rises when the woman is young, is single/divorced/widowed, is a dalit/adivasi/muslim woman, is a migrant, is less educated, has little access to alternate employment, and no access to unions.

This power imbalance is so stark and management’s action so ineffective and delayed that women fear raising a complaint could worsen their situation. This environment of intimidation leads to exploitation being the norm, accepted by workers without much resistance. It gives management a free hand when they want to increase productivity quotas, freeze wages and crush workers’ Right to Freedom of Association because workers fear that any opposition would only result in deterioration of their existing working conditions.

Fighting sexual harassment at workplace is therefore against the interest of employers. And , it is clear that an effective program to prevent sexual harassment at workplace requires not only a set of guidelines and directives but a transformation of the ethos and environment at the workplace. Most importantly it demands a reconfiguration of the power relations at a structural level.

This structural change can only be brought about by collective action of workers. But, to be the drivers of change, workers’ unions must begin with correcting themselves and put strict measures in place to check patriarchy that has seeped into their organisational structure. Only then unions will be able to demand an equitable workplace free of threat and intimidation.

What can Unions do?

The first step towards this change is to strike at the power imbalance between men and women in positions of power where men outnumber women, queer and trans people by a vast margin. Ensuring representation of people who are more vulnerable than others such as migrant workers, workers from religious minorities and marginalised castes and those who do not conform to the gender binaries at the helm of decision making positions can go a long way in formulating guidelines on prevention of sexual harassment. Unions must adopt a pro-active approach in this regard and change the existing hierarchy within its structure.

Further, safety mapping exercises should be carried out regularly to expose such work practices, procedures and geographical areas where vulnerable people feel more at risk of sexual harassment. Time bound and concrete plans should be devised to change them. Thereby changing the approach to mitigating sexual harassment from case to case basis to an overarching systemic approach where the priority should be prevention rather than redressal of the complaint post harassment.

And lastly, acknowledging the behemoth facing us it is important to design rigorous worker education programs for workers as well as their leaders aimed at abolishing prevalent gender stereotypes and prejudices which promote and reward masculine behaviour.

Fighting systemic inequity requires drawing long term strategic plans and willingness to make change, only workers’ unity can make it happen.