Naomi Klein in her 2007 book Shock Doctrine describes the ruthless strategy of governments across the world to push through fundamental pro-corporate measures at a time of collective shock – due to war, coups, terrorist attacks, market crashes or even natural disasters – when the people are disoriented and unable to respond. This strategy has been a key to the imposition of neoliberalism for several decades. This ‘Shock Therapy’ follows a clear pattern: wait for a crisis (or create one), declare the moment to be a time for “extraordinary politics”, suspend some or all democratic principles – and then push forward the corporate wishlist as quickly as possible.

Does this sound familiar? Especially in our present context? Our labour laws and our constitutional rights to life, to freedom of association and to equality before law are all being suspended in the name of the pandemic. Working people are scattered, bound at home due to the lockdown or still desperately trying to get there, unable to take to the streets in fear of the virus, jobless, disoriented, hungry, homeless. At this time state after state and the central government is pushing through their pro-corporate agenda – suspending labour laws, amending laws that govern right over commons, privatising public sectors. But this is one side of the coin which a lot of people are already talking about.

Are there any ‘Good’ corporations?

This article is about the other side of this very story – the story of the Good Corporations.We have often heard from workers that their employers are good employers – they not just are better employers on the shopfloor, but also contribute to the community – they run schools for underprivileged children, they run old age homes, so on. In this time of the pandemic we have seen many corporates donating monies to government, to non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to help people in distress. The Tatas have committed to pay Rs. 1500 crore to PMCARES, a fund created under the Prime Minister to be used for combatting the pandemic, Rs 1,000 crore by the Azim Premji Foundation, Reliance – 500 crore, Adani – 100 crore, JSW – 100 crore. Interestingly, while these corporates are contributing generously to this fund, many of them have declared that they do not have the money to pay wages to their workers in violation of the order of 29 March of the Ministry of Home Affairs directing payment of full wages to all workers for the lockdown period. Many employers have even gone to court and managed to convince the Supreme Court that they do not have money to pay wages.

| Group | Company | Action Taken |

| Tata | Vistara | 30% of its 4,000 employees have been sent on leave without pay from April to June |

| Tata | Taj Hotels | Employees have received an email from their CEO stating that if the travel ban continues, drastic steps would have to be taken |

| Azim Premji | Wipro | 300 employees of Wipro, in Pune filed a complaint of layoff at the labour department |

| Ambani | Reliance | Announced deferment of performance based pay (a considerable portion of the wage of most employees) and annual bonus (of the previous year) |

This list is never ending.

Thus the philanthropic commitments that Good Smart Corporates make in a time of crisis is one very important step to cover up their offences. While the Rs 1500 crores or the Rs 1000 crores look big as donations, it is a miniscule portion of what these corporations owe to their employees. H&M recently donated $500,000 to NAACP, ACLU and Color of Change that are working to fight racial discrimination in the US. This is a very noble cause but it is also about capturing the market through its commitment to this critical cause at this time of crisis. This donation is being made at the same time when 1300 workers are being laid off in a unionised garment factory in Srirangapatna, Karnataka that has solely produced for H&M for over five years.

Construction Workers’ Welfare Board

This was best understood many decades ago by the construction industry when they agreed to the demand for a construction workers’ welfare board for a meagre contribution of a 2% cess on their project value. Unions were happy and so were employers – it became a ‘win-win model’ which was then replicated in many sectors.

What was the problem with this model? This model allowed employers to get away with paying only 2% of their project value to the welfare board and not take direct care of any of the needs of their workers. All social security needs of workers got pushed to the board. The rampant accidents at construction sites also got pushed to the Board. Workers shifted their focus to the Board. Thus cost to company for workers’ health, safety and welfare all got reduced to the 2%. And today, as we see, even that cess remains unspent as most workers are not even registered under the board. The entire struggle against employers for better wages and working conditions got moved to the domain of a struggle with the Board and the government, while employers have gone

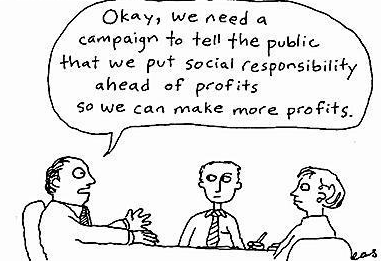

Thus donation not just serves commercial purpose it also serves the purpose of winning the favour of the recipient. When the recipient is government, the corporation litearally buys the favour of the government but when it is to non-governmental organisations, the corporation wins a good name within a community. This is a very important component of brand value for a company. The cost of earning a good name through donations is much lower than the cost of abiding by the law and internationally accepted core standards of employment and working conditions to all employees.

In India, the Companies Act in April 2014, mandated businesses with annual revenues of more than Rs. 1000 crore to give away 2% of their average profit of three years to charity as Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Following this most of the big companies set up their own charitable foundations and directed this fund to their own charity initiatives that will help them advance their own cause.

CSR of course is not an Indian phenomenon. India is only one of the countries that legally mandates it for big companies.

According to the 2018-19 CSR report of Tata Steel their CSR fund is used to:

- promote health care including preventive Healthcare and Sanitation; promote education including special education;

- promote employment enhancing vocational skills especially to Women, Children, Differently abled and in Livelihood projects;

- promote environmental sustainability, protection of flora & fauna, agro forestry, animal welfare, resource conservation, maintaining quality of soil, air, water; and

- protection and restoration of national heritage, promotion of art, culture, handicrafts, setting up public libraries etc

all in the two states of Jharkhand and Odisha. Ever wondered why this focus on only two states and not in other poor states? Most of Tata Steel’s production comes from their plants located in Jamshedpur in Jharkhand and Kalinganagar and Dhenkanal in Odisha and their raw material from their captive mines in these two states.

In January 2006, about 1000 adivasi villagers gathered with lathis, axes, bows and arrows in Kalinganagar and opposed the construction of the boundary wall of the Tata steel plant that had encroached into their village which was on forest land. The National Green Tribunal had also issued a notice to Tata Steel and the Odisha government against this construction but the Tatas started their construction. Over 500 armed police personnel open fired on the villagers and 13 of them were killed. But today after 14 years, the Tata Steel plant stands there and the story of the lost lives is lost to most people just like the story of the entire forest area and villages that were wiped off to create the Tata Steel city of Jamshedpur over a century ago. The people’s resistance, their lives, their livelihood, their culture, their arts and craft, their families have got wiped from history and what remains today is all the good work that the Tatas continue to do in these two states to make people forget how they came to be there. The people of these villages have been rendered landless, converted to low paid migrant workers in other cities or contract workers in the steel plant, their children will be dependent on the Tatas for basic necessities. This is a standard CSR model – give alms to places and people, from where you make your profits.

CSR has another very critical purpose – wiping out guilt of consumers. Today’s consumers, especially in the global north, expect responsibility, action, and accountability from businesses and tend to shop at companies that share their values. This is one way to deal with their own guilt – the guilt of knowing how these products are produced, the guilt of knowing why these products are so cheap and keep getting cheaper, the guilt of having a life better than many many others, the guilt of how the money is earned that makes the life better than so many others. CSR is the answer to this guilt. It creates a ‘feel good’ sense that gives the consumer a justification to indulge in consumerism. Consumerism then even becomes a mean for supporting a social cause and hence becomes a win win solution for guilty consumers and the company which manages to sell more.

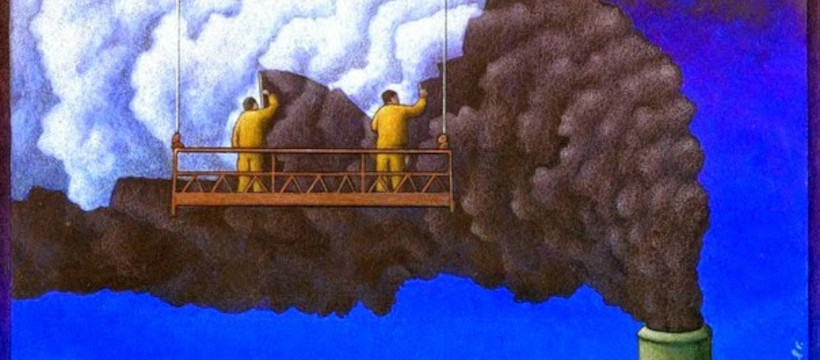

Obviously CSR is not about doing good but is about showing good – CSR is the smokescreen that hides the exploitative models of production that creates the profit. Thus 2% of the profit is used to camouflage how the remaining 98% is created.

CSR in the time of Pandemic

CSR is the other side of the shock therapy that we are facing post pandemic. While the government is working over time to eliminate all protections for workers, CSR acts as blood money being mobilised within society to quell any form of resistance. The funds are used to infiltrate social movements against corporates and control and corrupt these. It even comes in the guise of support for democratic movements and makes the recipients dependent and destroys democratic initiatives.

CSR is not a harmless friend that we can rely on for support – it is far more dangerous than the monster it represents. Corporates use repression and control to break resistance on

shop floors and other workplaces. These repressive measures often create conditions in which workers come together to resist. But CSR breaks social opposition without use of force. It corrupts and co-opts and allows social movements to disintegrate. It works with our children, our community and creates a make believe world of happiness while the profiteering continues within the business model.

It is thus not surprising that CSR is prolifertaing in this time of pandemic. Charitable foundations are helping migrants reach their homes while the parent companies of these foundations keep creating the conditions that are forcing the migrants to escape the cities.