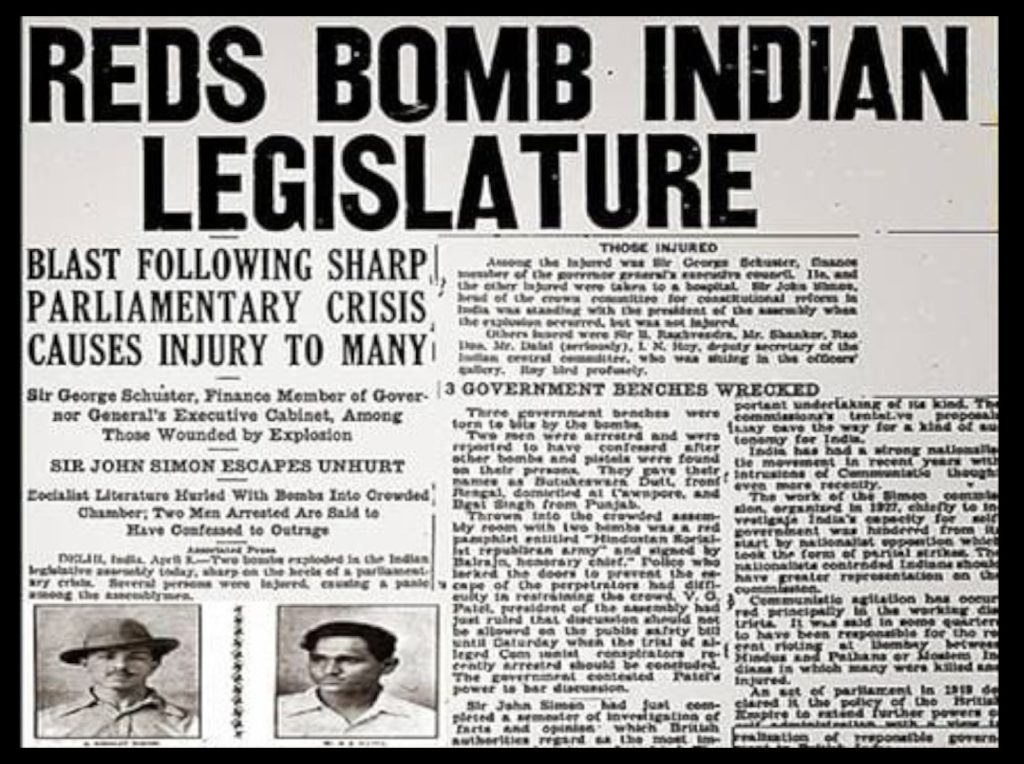

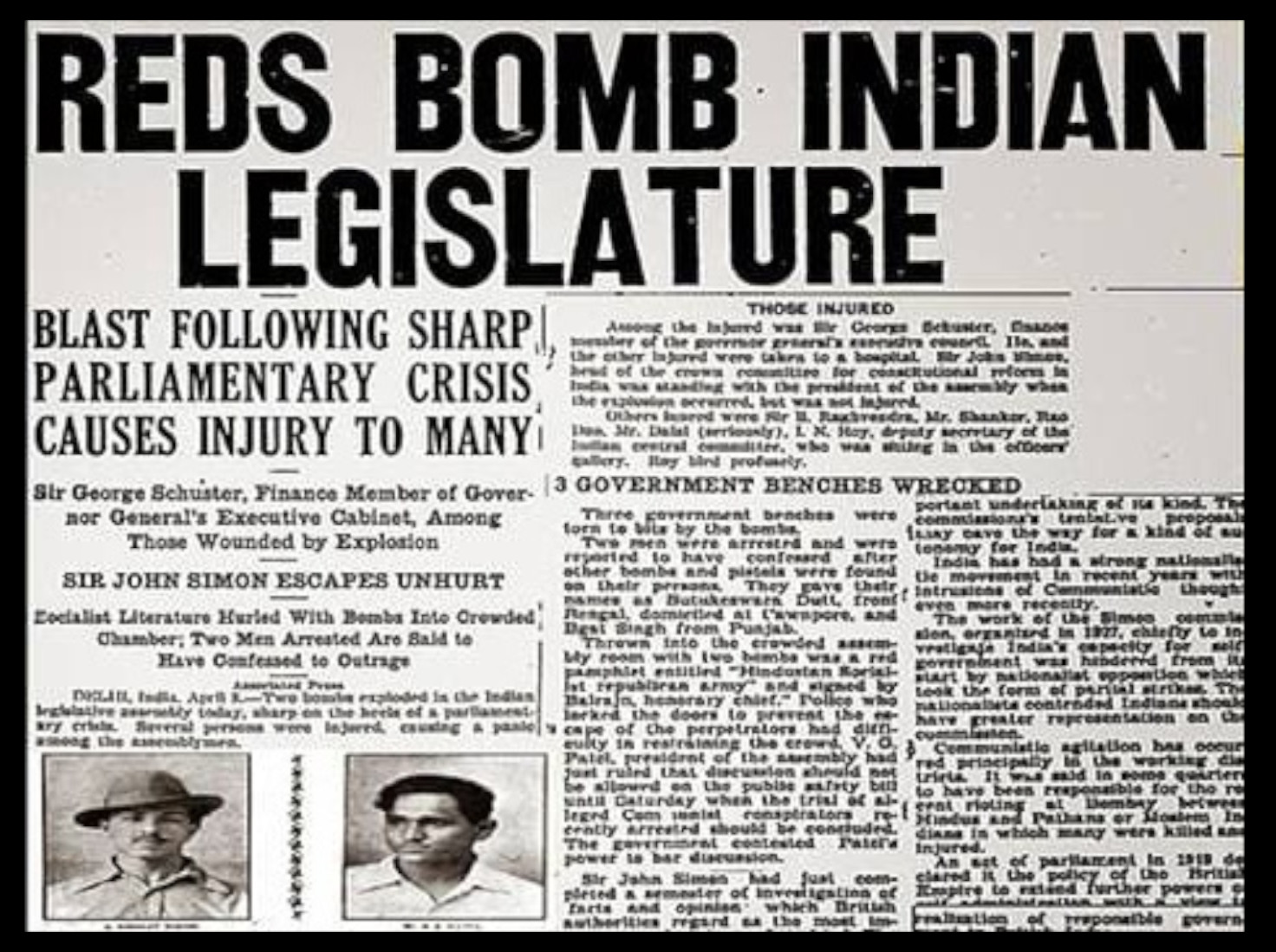

On 8 April 1929, the British imperial government in India tried to pass the controversial the Trade Disputes Bill relating to conditions of employment and resolution of disputes between employees and their employees. Interestingly despite the united opposition to the Public Safety Bill tabled on the same day, when it came to protecting the rights of workers the legislators were divided and the British government was able to get it passed with 56 votes in favour to 38 against it. Among those present and voting were Motilal Nehru, Vallabhbhai Patel, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Madan Mohan Malaviya and others. When Vithalbhai Patel, the then President of the Central Assembly, was about to announce the results of voting on the Public Safety Bill, two bombs were thrown into the assembly hall from the visitors’ gallery by Bhagat Singh and Batukeshwar Dutt along with loud cries of Inqilab Zindabad! and Workers of the World Unite! These were accompanied by red flyers against the two Bills. Singh and Dutt could escape after the bombing but they courted arrest and announced that their act was intended to disrupt the proceedings of the assembly in order to stop the two draconian laws being passed.

What was in the Trade Disputes Act, 1929?

In 1906, British parliament, with a Liberal party government and, for the first time, with a substantial presence of the Labour Party, passed the Trade Disputes Act providing trade unions with immunity from liability for damages arising from industrial and other employee actions. This was an outcome of the continuous campaign by trade unions against the Taff Vale judgement of 1901 that established trade unions as legal incorporated entities and as such were liable to pay for employers’ losses that may arise from strikes. The decision was potentially crippling for the unions and their members. The new law reversed the Taff Vale judgment and provided unions with complete immunity from liability for civil damages, including providing some degree of immunity to individual trade unionists and some legal protection for peaceful picketing.

With the Conservative Party coming back to power in 1924 with Stanley Baldwin as the Prime minister and Winston Churchill as the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Britain embarked on a disastrous economic path of lowering miners’ wages and worsening their working conditions leading to the miners’ strike in 1926. The British Trades Union Congress (TUC) gave a call for a General Strike in solidarity with the mine workers. In response, the Conservative Government passed the Trade Disputes and Trade Unions Act, 1927 which outlawed general strikes and sympathetic strikes, mass picketing and banned civil servants from joining trades unions affiliated to the Trades Union Congress.

As a last act before losing in the general elections in May 1929, the Conservative government pushed through the Trade Disputes Act of 1929 in India that banned strikes, prohibited one union from supporting another effectively outlawing secondary picketing, prohibited civil servants from becoming members of a political party and prohibited workers from making financial contributions to political parties. It required a 15-day written notice for strikes and lockouts in public utility services. This too was in response to the rising strikes across the textile mills in Bombay demanding recognition of the Girni Kamgar Union, a stop to arbitrary victimisation and dismissals of and reinstatement of the workers who were terminated because they were office bearers of the union. The number of workdays lost in Bombay city itself in 1928 to industrial actions was 31,647,404 days. The Workers of the World Unite call by Singh and Dutt at the Assembly was in solidarity with the British working class also being suppressed by the same law.

The Bombay Millowners’ Association in its Report for the year 1928 says: “…Your Committee naturally supported the principle underlying the Bill, … Committee laid special stress was the necessity of incorporating in the Bill, special provisions for controlling picketing. What is now erroneously called “peaceful picketing” does not really exist. Picketing is picketing at all stages and under all conditions, even though disguised under the more harmless terminology of “gentle persuasion”. It is intimidation pure and simple, often accompanied by excesses which are as unfair in their nature as they are tyrannical in their effect. Your Committee have accordingly made a strong and emphatic recommendation for stopping it or at least for controlling it so as to prevent it from degenerating into coercion and intimidation”.

The report goes on to add: “…we want peace and goodwill; and that we don’t want to fight. But, if in our own interests and for our very existence, we are forced to do so, we shall fight with our backs to the wall. We will not tamely allow an industry in which over 60 crores of rupees have been sunk and which we have taken half a century to build up with such labour and sacrifice to be ruined by the idiosyncracies and caprices of those who have set themselves up as labour leaders, but who apparently are guided and led by revolutionary organisations outside the country.” This attitude of the millowners was reflected in the divided voting in the imperial Central Assembly, where Indian legislators voted in support of the Trade Disputes Act to protect the interest of the Indian industrialists and Singh and Dutt bombed the Assembly in protest.

Why is this relevant today?

The new Industrial Relations Code 2021 recognises and gives credence to this century old paranoia of employers about all forms of democratic protest ranging from factory gate protests and pickets to strike action. From expanding the notice period for strike action from 15 days in public utilities to 60 days in all industrial establishments, the law makes it almost impossible for workers to go on strike. In addition, if a strike at any point is declared illegal, the trade union engaged in it, under the new code, can be de-registered. This in turn means that the trade union nor its office bearers will no longer enjoy civil immunity pushing workers’ struggles outside the framework of justiciable law. The Code brings back into law what Singh and Dutt gave up their lives fighting for.