Article 19(1) of the Constitution states: “All citizens shall have the right … (c) to form associations and unions”. Despite this India has, over the years, resisted ratification of Conventions 87 and 98 of the ILO on the right to freedom of association and collective bargaining. In a PIB release of 2017, the government of India publicly stated that: “The main reason for non-ratification of ILO Conventions No. 87 & 98 is due to certain restrictions imposed on the Government servants. … the ratification of these conventions would involve granting of certain rights that are prohibited under the statutory rules, for the Government employees, namely, to strike work, to openly criticize Government policies, to freely accept financial contribution, to freely join foreign organizations etc.”

What is a trade union for?

The Trade Union Act, 1926 was a distinct piece of legislation that provided workers (and employers) the right to form unions. It was not only bodies that will come into action in times of dispute. Trade unions are organisations that function whether or not a dispute exists with the employer. The merging of the Trade Union Act with the ID Act, 1948 in the Code on Industrial Relations binds trade unions to a narrow scope of a dispute resolution framework, and limits the wider political purpose of a workers’ organisation.

Section 2(b) of the TU Act defines a trade union as, any combination, whether temporary or permanent, formed primarily for the purpose of

- regulating the relations between workmen and employer

- or between workmen and workmen

- or between employers and employers

- or for imposing restrictive conditions on the conduct of any trade or business

and includes any federation of two or more trade unions.

In the statement of objects and reasons of the original legislation, it was clearly stated, that there shall be no restriction placed upon the objects which a registered Trade Union may pursue, but the expenditure of its funds must be limited to specified Trade Union purposes. Thus even the British colonial government did not intend to put restrictions on the work that a trade union may pursue and who might form and join a trade union.

The standard objectives that unions pursue as suggested by the Model Constitution of a trade union are:

- To regulate terms and conditions of employment

- To improve the working conditions at work place.

- To raise the living standards of workers.

- To protect the workers by exploitation of management.

- To help in maintenance of discipline of organisation/industry

- To ensure the proper implementation of personnel and welfare policies.

- To replace managerial dictatorship by workers’ democracy

- To establish industrial peace by improving employee-employer relations.

- To act as a best negotiator machinery.

- To safeguard the interest of organisation and organisational health.

- In a broader sense, to protect the interests and welfare of workers.

The AITUC, which was formed in 1920, aimed to establish a socialist state in India; to socialize and nationalize means of production, distribution and exchange; to abolish political or economic advantage based on caste, creed, community, race or religion; and to secure and maintain for the workers the right to strike, among other objectives.

In 1947, when the INTUC emerged out of the AITUC under Congress party leadership, the newly formed national federation made their political objective to align with the new government clear in their constitution. The INTUC aimed to establish an order of society which is free from hindrance in the way on an all round development of its individual members, which fosters the growth of human personality in all its aspects and goes to the utmost limit in progressively eliminating social political or economic exploitation and inequality, the profit motive in the economic activity and organisation of society and the anti-social concentration in any form; to place industry under national ownership and control in a suitable form; To develop in the workers a sense of responsibility towards industry and the community; and to raise the workers standard of efficiency and discipline. This was shift away from the militant revolutionary objectives of the AITUC towards a more industry-friendly union principle. And in 1955, Dattopanth Thengadi, a RSS pracharak, founded the Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh (BMS), with the objective of (i) establishing a Bharatiya order of a classless society in which there shall be secured full employment; replacement of profit motive by service and establishment; of economic democracy; development of autonomous industrial communities — with each one of them consisting of all the individuals connected with the industry as partners; (ii) assisting workers in organising themselves in trade unions as a medium of service to the motherland irrespective of faiths and political affinities; (iii) securing the right to strike, and (iv) inculcating the spirit of service, cooperation and dutifulness in the minds of the workers and develop in them a sense of responsibility towards the nation in general and the industry in particular. Thus formation of trade union federations have always been along ideological lines – their idea of society, polity, economy.

Thus the trade union was never meant to be a body only meant for negotiating disputes. It was a body that was meant to serve a larger purpose of political education of the working class and mobilising them for achieving the stated goals. The objectives of a trade union were not even restricted within the framework of existing laws – it was a body that could fight collectively for new laws that would serve the interest of the working class.

Trade union objectives can be divided into two broad categories: (a) economic, that have financial implications for the employer; and (b) social and political that are linked to the larger social and political issues that affect the working class. Thus, merging the ID Act with the TU Act within the new IR Code is a covert effort to control the political activities of trade unions. How does this happen?

Under Section 9 (5)(ii) of the new IR Code, the registration of a trade union can be canceled if the trade union contravenes the provisions of this Code or the rules framed under the Code or its own constitution or rules. This clause was identical in the Trade Unions Act but when copied ditto into the IR Code, its meaning has gotten widened – now it means contravention of not just the sections of the TU Act but also that of the ID Act.

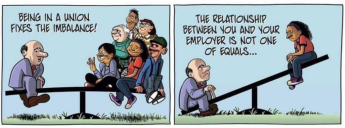

Under the two separate laws, a trade union had the power to call for industrial actions, which could be termed illegal under the ID Act, but that did not have any impact on the registration of the union itself. The right of the workers to their union was protected under law and the constitution. A dispute with an employer could not lead to a situation where the government could take away the right of workers to their own union. What the merger of the laws has meant, especially in the context of Section 9 (5)(ii) of the IR Code, the government now legally has the power to tilt the balance of power further in favour of the employers by taking away the right of workers to come together.

Specific to the right to strike: the power of trade unions to exercise this right has been drastically curtailed under the new Code. Under the ID Act, workers in a public utility had to give a 15 day notice to go on a strike. This provision was to ensure the right of citizens to the public services and public goods provided by the public utility. This came from the idea that while the workers of public utilities should have the right to strike for their own demands, their actions should not disrupt the lives of citizens who are dependent on them. This period of notice allowed the public utility to either resolve the crisis within this period or make alternate arrangements for the citizens. But this clause has now got extended to all enterprises – basically extending this leeway to even luxury goods and services. The Code further states that the moment a strike notice is given, the dispute should be taken up by the labour department for conciliation. The code further prevents workers from going to strike while conciliation is on. Any strike in this period will be declared illegal. And once a strike is declared illegal, the trade union engaging in it, can lose its registration, as it will be in violation of the provisions of this code. This therefore more or less creates an institutional framework that does not allow a strike. Or creates a framework in which strike action can be taken by non-trade union platforms that will not enjoy the immunities under the IR Code that a trade union can access. This will lead to individual cases against trade union activists leading a struggle outside the trade union framework. It is thus a circular situation that has been very cleverly created which will prevent strikes any which way.

Who can form a Trade Union under the IR Code?

The Trade Union Act was legislated in 1926, in response to the series of strikes across the country that was termed as the ‘Cawnpore Conspiracy Case’ of 1924, which accused prominent trade union leaders and activists of attempting a communist revolution to overthrow the British government. The TU Act in 1926 was meant to regulate and monitor the functioning of trade unions in the country. The TU Act even predates the Trade Disputes Act, 1929 that is the precursor to the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947. Thus the definition of a workman under the TU Act predates that of the ID Act, and allowed for a much wider scope of inclusion than that allowed under the ID Act. The TU Act even allowed employers to register their own trade unions.

The new IR Code claims that it removes all inconsistencies that existed due to multiplicity of laws. However, in the context of defining a worker, the Code itself incorporates two definitions: (i) to apply to all chapters of the IR Code except Chapter III; (ii) to apply solely to Chapter III, that is the chapter that deals with the trade unions. Specifically for the purpose of Chapter III, the IR Code defines a worker as:

(i) all persons employed in trade or industry; or

(ii) persons defined as a worker under section 2(m) of the Unorganised Workers Social Security Act, 2008. The only thing one can say in this context is that the framers and the legislators who passed this code in a super hurry seem to have forgotten that the Social Security Code repealed the Unorganised Workers’ Social Security Act. If we look at the Social Security Code, there are 9 definitions for a worker:

(i) section 2(7) building worker; (ii) section 2(19) contract labour; (iii) section 2(35) gig worker; (iv) section 2(36) home-based worker; (v) section 2(41) inter-state migrant worker; (vi) section 2(61) platform worker; (vii) section 2(75) self employed worker; (viii) section 2(86) unorganised worker; and (ix) section 2(90) wage worker. Nowhere does the Social Security Code state which is the one that has replaced section 2(m) of the Unorganised Workers’ Social Security Act, 2008.

This multiplicity and circularity of definition within the same code and between codes will necessarily create problems vis-a-vis recognition of a certain category of workers as ‘workers’ under the IR Code thereby making the process of trade union registration for workers in not clearly defined categories such as honorarium workers, sex workers, domestic workers, more difficult.

What can a trade union do?

With hands and feet tied by the new code, should a trade union close shop and retire? Of course NO. The job of a trade union has not changed even if the law governing it may have. The primary purpose of a trade union is to fight for the rights of workers and protect their interest in every possible way. No law has been created in history of the world that favours workers unless there has been a movement to push the government to change its position.