In India, the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act of 2005 ensured a legal right to all adults in rural areas to access 100 days of manual work per family at a notified wage. This law relatively reduced distress migration from rural areas, increased the prevailing rural wage, set a work standard for rural works, equalised wage for men and women in rural areas thereby increasing family income. With the focus on NREGA declining for the subsequent government and the budgetary allocation for it stagnating along with non-implementation of the programme and delay in wage payments, rural distress has once again spilled over to the urban centres.

In addition, the urban centres have not been able to absorb either the existing urban working population or the ever flowing rural migrants in search of livelihood. However the condition in the rural areas with negligible opportunity for employment, migrants, even if they do not find stable employment in the urban centres, do not migrate back to their rural homes. What develops as an outcome, is they add themselves to the already existing army of self employed workforce in the urban centres exploiting their own labour and that of their families, surviving on the brink of absolute poverty. The now illustrious entrepreneurship model of a ‘chaiwallah’ or the ‘pakodawallah’ made famous by the honourable prime minister is the story of this model of survival. We see these ‘successful’ entrepreneurs all around us – the vegetable vendor from Bengal in Delhi who brings vegetables to our doorstep, the golgappa boy from Banaras who dropped out of school when his father died to feed us the most delicious golgappas at the street corner of the local market, and of course the oriya plumber who sits at the local hardware shop all day waiting for phone calls from the local flats for repair jobs. The funny twist of fate is that if any of them are offered a stable and secure wage employment, they would all abandon their roaring profitable business and their freedom and choose the ‘bonded’ life of a waged worker. This is the real world of surplus labour. Surplus labour is invisible in an economy because everyone ends up doing something to stay and keep their families alive. This has been glorified by many as self-employment, some as entrepreneurship and some as path to women’s empowerment. This glorification is capitalism’s way of keeping its pool of surplus labour so that wages remain suppressed. As wage labour demand higher wages, there is always this pool of self employed who are willing to offer their labour, at a lower rate which not just keeps the wage at the minimum, it also keeps the minimum at bare subsistence.

But what if this huge pool of surplus labour was offered a choice between a job gurantee and a Universal Basic Income?

Universal Basic Income – Sheep in Wolfskin

Universal basic income is a government-guaranteed minimum income that is paid out to a citizen to cover the basic cost of living and provide financial security. There may be specified criteria for eligibility of this payout but it is universal within that group, irrespective of whether the person is employed or not.

Universal Basic Income is not a very new concept. In a speech in 1967, Martin Luther King Jr. said: “ … We are demanding an emergency program to provide employment for everyone in need of a job, or if a work program is impractical, a guaranteed annual income at levels that sustain life in decent circumstances. It is now incontestable that the wealth and resources of the United States make the elimination of poverty absolutely practical.”

Martin Luther King Jr. fought racism, but unfortunately, not capitalism. Thus his proposition for guaranteed income only looked at reducing economic inequality between the coloured people and the whites in the US. He was willing to accept that jobs will be lost and not created with advancement of technology and capitalism and hence the proposal for the guaranteed income. The guranteed income was not just meant to eliminate poverty, it was to make the poor, consumers to fuel capitalist growth.

In six decades since King Jr., the concept of universal basic income (UBI) has not progressed much. It still remains an integral element of sustaining capitalism. It is proposed as a welfare measure for elimination of poverty, but what it is meant to achieve is to (i) increase market access of people by providing liquid cash in the hands of the poor so they can afford small packets of toothpaste, small packets of jam and ketchup, detergents, even cheap packaged junk food, visit private doctors, send their kids to private schools to keep these industries afloat; (ii) dismantle public provision of goods and services; and (ii) more importantly, avoid riots and strife in a chaotic desperate society. It is meant to be a safety valve in a capitalist society. This is the other side of the glorification of entrepreneurship in a capitalist society.

Social Security Net: The concept of UBI also needs to be looked at in the context of where it is being proposed to be rolled out – a rich country with some poor people or a poor country with some very rich people. Germany, like other countries earlier, recently initiated a 3 year trial as a part of which 120 people will receive €1,200 each month – an amount just above their poverty line – and researchers will compare their experience with 1380 others who shall not receive this amount. What is important to note here is that the 120 persons who are being provided the UBI are being paid an amount that is just above the poverty line. This implies that these 120 individuals are in a state that first of all they should not be in, in one of the richest countries in the world. The cash payout made to these 120 persons should have been part of the social security net through which they should not have fallen. Thus what is essential is not the cash handout that keeps them just above the poverty line, but a non-cash social security net that provides basic necessities to people below a certain income level. Replacing a social security net such as unemployment benefit in the global north, or the food ration through the public distribution system as in our country, with a cash outlay does not necessarily lift a certain section of the population out of poverty.

Public Provisioning and Corruption: People who came up with these ideas of public health system, public education system, public transport, public distribution system were neither complete idiots not crazies who had no idea what they were doing as governments today across the world would like us to believe. These systems are portrayed as dens of bureacratisation and corruption that must be eliminated to ensure a clean world. But these were meant for the benefit of the many, and not just the few. This was an alternate model to the model of concentration of wealth for the few.

When a government hospital refuses treatment for a critically ill patient, the patient is moved to a private hospital. The doctor denying treatment is termed a corrupt doctor and it seems the story ends there. It is only the beginning of another story where this doctor recieves a payout from the private hospital where the patient is recommended to go. The doctor is undoubtedly a part of a corrupt system, but the private hospital is the architect of the corrupt system. Corrupting all that is for the many, schools, hospitals, even government administration, is core to the profit making philosophy of capitalism. This also extends to the repeated effort of governmentto replace hot cooked meals at anganwadis with biscuit packets. Thus undermining public services is not just done by capital but also by the capitalist state.

With the most powerful attack launched on the idea of collective welfare since the 1990s, we have today reached a point where we can see no alternative model of development. The alternatives have been successfully discredited and destroyed. In such a vacuum of possibilities, it is difficult for us to see the wolf in the sheepskin.

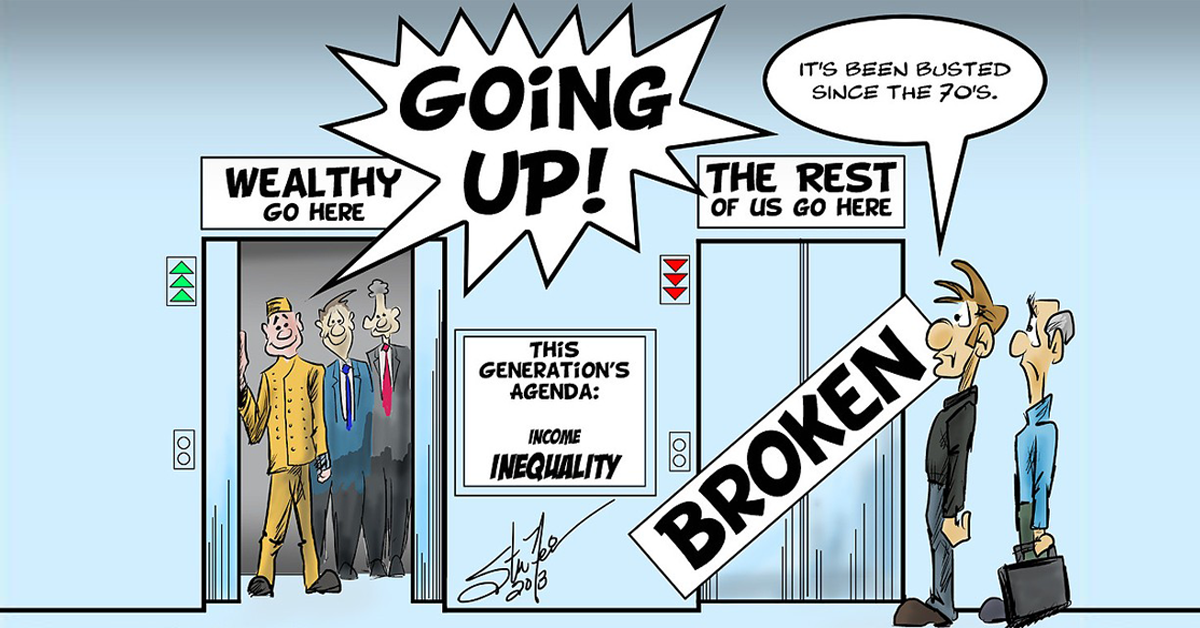

Inequality: The 2019 Oxfam report on inequality showed that India’s top 10% holds 77.4% of the total national wealth, while bottom 60% population holds only 4.8% of the national wealth. UBI, if ever to be proposed in a country like ours, would mean providing a certain sum of cash to this over 60% of the population. The quantum of money that will be required to hand out this bare minimum cash outlay for all in this category, it would mean this cash dole will replace every other public provisioning – for health, education, food, housing, transport, given the budgetary constraint. So the larger question that UBI brings to the table is should UBI replace every government responsibility for people’s welfare?

Public Goods: Finally, we come to the question of why we need non-cash public goods and services? And can private players successfully replace the government in the provision of public goods? In economics, a public good is defined as a good or service which no person can be excluded from, and its consumption by one person does not reduce its availability for others (like mother’s love). Let us first take the simple example of street lights. When a certain street is lighted, the lights are there for all who walk that street and not just who live on that street, and it does not switch off when 100 or 200 people have walked that street to prevent others from using it. The street lights not just make it easier to navigate that street it also ensures safety of an entire community. The value of both of these are immeasurable. If we try to put a price for its provision no one will be willing to pay as everyone can claim they do not use that street and will know that it does not matter whether they pay or not, the light will still be there. As a consequence, the provider of this good cannot make profit out of this. Hence no private player will be willing to provide this good that brings safety to a community as it does not bring profit. So how can this be priced? Hence street lights are provided by local government and its cost is derived from the budget allocation.

This also applies to nutrition, health, education, mobility, whose value, like safety, is immeasurable, and therefore cannot be relied upon the private sector to provide for all. The value derived from these goods and services is far more than can be ascribed to them and is even higher that the price at which it can be delivered. If delivered by the private sector, to make profit, they will put a price on it, which will be affordable for a few and not for many. This will lead to exclusion and this exclusion will lead to expanding inequality. What this exclusion will also mean is a country with malnourished children with low immunity, who will lack education and capacity to learn skills, undernourished mothers who will give birth to undernourished children, some of who may not even survive till adulthood. What we have achieved in the decades following independence despite the crumbling public health, public education, public employment, public transport systems is incremental improvement in our intergenerational health and education parameters, of improved quality of life for all, even if very slowly. What privatisation and jobless growth will together bring is a drastic decline of all this.

Dignity: And finally, people on the brink of poverty may accept a guranteed income to stay afloat, just like they ‘opt’ for self exploitation. This cannot be represented as a choice they have voluntarily made. A voluntary choice can only be made when more than one option is available. When workers accept a ‘basic income’, it is not indicative of their preference for it. It is only a choice they exercise between hunger and this basic income. Question is do they stop looking for employment when they start receiving this basic income – NO. Even the policymakers who design basic income models claim that it helps workers to choose jobs better. This clearly indicates that workers do not want dole, but always prefer a safe and secure waged employment with regular working hours, weekly off, basic healthcare, and minimal retirement benefit.

This brings us to the critical issue of dignity. Are we supposed to assume that since a group of workers are extremely poor, they do not have the right to a life with dignity? Does the constitution of this country not make us all equal and guarantee all of us the same life of dignity? The limited employment guarantee law in our country provided workers for the first time in rural areas a sense of dignity.

Interaction with women among the working poor often reveals that cash is controlled by men in patriarchal societies and hence is used according to their priorities, while if government provided food coupons it ensures nutritional standard of the family, increased outlay for public health services, public education, public distribution system, public transport system, it would improve the overall condition of the society by providing a social security net that will keep them afloat at all times without losing their dignity.