The Code on Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions replaces:

| Following Acts: | |

| 1 | The Factories Act, 1948 |

| 2 | The Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act, 1970 |

| 3 | The Inter-State Migrant Workmen (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act, 1979 |

| 4 | The Building and Other Construction Workers (Regulation of Employment and Conditions of Service) Act, 1996 |

| 5 | The Mines Act, 1952 |

| 6 | The Plantations Labour Act, 1951 |

| 7 | The Beedi and Cigar Workers (Conditions of Employment) Act, 1966 |

| 8 | The Dock Workers (Safety, Health and Welfare) Act, 1986 |

| 9 | The Motor Transport Workers Act, 1961 |

| 10 | The Cine-Workers and Cinema Theatre Workers (Regulation of Employment) Act, 1981 |

| 11 | The Sales Promotion Employees (Conditions of Service) Act, 1976 |

| 12 | The Working Journalists and other Newspaper Employees (Conditions of Service) and Miscellaneous Provisions Act, 1955 |

| 13 | The Working Journalists (Fixation of Rates of Wages) Act, 1958 |

The 13 laws together add up to 241 pages of hard won rights of workers, through major struggles, at the cost of several thousands of lives lost due to unsafe working conditions, at the cost of the lives of workers and their families who lost their capacity to work and provide for their families. With one sweep of a magic wand these have been wiped away by the 86 pages of the Code. The 86 pages retains a lot of the words that were used in the earlier laws but changes some words that critically bestowed rights upon workers that protected their Right to Life as guaranteed by Article 21 of the constitution.

Right to Life

Article 21 of the Constitution states that “No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to the procedure established by law.” In the case of Kharak Singh v. State of Uttar Pradesh, the Supreme Court held that the term “life” means more than mere animal existence. The inhibition against its deprivation extends to all those limbs and faculties by which life is enjoyed. And in the case of Oliga Tellis and Ors vs. Bombay Municipal Corporation and Ors, the court held that the right to life included right to livelihood. However, the court said that no person could claim the right to livelihood by the pursuit of an illegal occupation. If we read our fundamental right to life along with these two critical orders what we can conclude is that every person enjoys the right to livelihood in a safe and secure environment. Anything that prevents it is in violation of our constitutional right.

Legally Binding laws vs Non-binding Rules

The Code on Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions (henceforth CoOSH) by removing the critical binding clauses, that set a minimum standard for safety at work and basic facilities such as drinking water, toilets, wash rooms, locker rooms, etc., which ensure the right to life of workers at a workplace, protecting their life and livelihood.

Soon after assuming office, Prime Minister Narendra Modi likened maintenance of boilers to that of a privately owned car, where owners should be trusted to do their best because they understand the need for safety in its operation. Even if we leave out the numerous lives lost everyday in construction sites, sanitation work, and other workplaces, in the last six years, since self certification has been introduced in workplace safety standards, the number of massive accidents have increased drastically. In the last few years we have had the blast at the Unchahar power plant in Rae Bareili, UP in 2017 that killed 32 and seriously injured many; fire at the fire cracker factory in Bawana, Delhi that killed 17 workers in 2018 and again injured several others – this factory did not even have the proper license to operate; in 2019 an explosion in a chemical factory in Dhule killed 13 workers, injured 72 others. In 2020, the number of major accidents since the lockdown was lifted has become unprecedented owing to the lack of maintenance of the plants and equipments during the period of the lockdown. In the rush to restart operations, employers restarted functioning in plants without making appropriate provisions for safety. This was possible due to the progressive reduction in the power of the labour inspectorate and through the process of self declaration. The result has been a loss of large number of lives.

| States | City | Date | No. of Deaths | Injured | Cause | Company |

| Gujarat | Vadodara | 11-Jan | 8 | 6 | Explosion | Aims Industries |

| Maharashtra | Boisar | 11-Jan | 8 | 7 | Explosion | ANK Pharma |

| Haryana | Bahadurgarh | 28-Feb | 6 | 28 | Explosion | Diester Chemical |

| Andhra Pradesh | Vishakhapatanam | 07-May | 12 | – | Gas Leak | LG Polymer |

| Tamil Nadu | Neyveli | 07-May | 5 | 3 | Boiler Explosion | Neyveli Lignite Power Plant |

| Gujarat | Bharuch | 03-Jun | 10 | 50 | Boiler Explosion | Yashaswi Rasayan |

| Tamil Nadu | Neyveli | 01-Jul | 13 | 10 | Boiler Explosion | Neyveli Lignite Power Plant |

| Uttar Pradesh | Ghaziabad | 05-Jul | 8 | 3 | Fire | Illegal Candle Factory |

| Maharashtra | Nagpur | 1-Aug | 5 | Several | Boiler Explosion | Manas Agro Industry and Ifrastructure |

| Telangana | Srisailam | 21-Aug | 9 | 3 | Fire | Srisailam Hydro Power Plant |

The increase in the number of accidents for the last five years was in violation of the intent of the original laws that governed safety and security in workplaces. What this means that when such an accident ocurred, the investigation invariably showed that some specifications of the binding Factories Act or Boilers Act or Mines Act or Building and Construction workers act have been violated which resulted in the accident. This legally justified the claim of workers to compensation, their demand for putting in place the missing systems as per the law.

This obviously posed a problem for employers. These provisions of the law attributed direct responsibility of the accident at a workplace on the employer. The individual workers could not be blamed for a boiler explosion or a mine collapse because they turned on a switch or walked into a collapsing floor of a coal mine. The responsibility for maintenance of the plant and providing safety parameters to workers, including training, rested with the employer.

The Code on Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions with a swish of a magic wand has shifted the legally binding requirements under the different laws that determined working conditions in different workplaces from the laws to the rules. Thus there is no longer any basic minimum standard of work applicable across the country that is legally binding on employers. Successive governments at the centre and different governments in the different states can also change the minimum standard as labour is a subject on the concurrent list of the constitution. For example, Section 11 of the factories act made it mandatory in all establishments to have the floor of every workroom be cleaned at least once in every week by washing, using disinfectant, where necessary, or by some other effective method. Now this is no longer specified in the law. It may find its place in the rules or even not. What that will mean is that this critical and basic provision that ensures basic hygiene in the workplace can now be changed from time to time to suit employer pockets. Thus the laws that were legislated to protect workers have been transformed to become laws that will protect employer interest and their already deep pockets.

Hazardous Industries – Who is Accountable?

To make matters worse, the special amendments that were brought into the Factories Act after the Bhopal disaster have been severely compromised in the new Code. These amendments had given state governments the power to amend the list of industries involving hazardous processes which gave states the power to review industries and declare certain industries to be hazardous.

This power of the state governments has now been replaced by the power to change the permissible limit for hazardous substances used in a certain process. Harmless as it may sound, this will force states to compete against each other for investment by lowering these limits thereby endangering the lives of not just the workers but all who live around a plant to entice investment. As the focus for changing the law has shifted from providing protection to workers to providing a conducive environment for investors, this ‘empowerment’ of the states is to encourage a race to the bottom for which the central government will not take ownership.

The terrible industrial disaster at the Union Carbide pesticide plant in Bhopal, changed the life of over 500,000 people who were exposed to the toxic methyl isocyanate gas as well as the generations to come. In a series of studies conducted by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) in years following the gas leak it was found that Methyl isocyanate damages human DNA and thereby the impact of the gas leak continues even today.

What this terrible tragedy exposed to the world is the duplicity of multinational companies regarding safety provisions practiced in their plants in their home countries or other countries in the global north and the practices in plants in the global south. Companies move from locations with higher safety standards which require higher investment to locations with lower safety standards. That is today the logic of the entire framework of a supply chain. Companies produce various components of their product at various locations in the global south where wage cost is low but so is the cost of life.

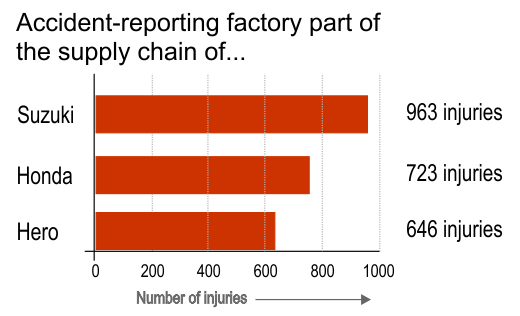

A report by Safe in India (2019) documented 1,369 accidents in the auto hub in Gurgaon since December 2016. According to this report, most of the accidents took place because of a combination of the following factors: safety mechansims were not functioning properly; machine malfunction; no protective equipment; no training of workers. Most of the factories where these accidents were reported belonged to the supply chain of three auto majors in the Gurgaon hub as shown in the graph

As we see in this case, the firms with differential standards within the supply chain of an MNC does not even need to be in different countries. They can be located in the same region but on a lower tier than the mother plant.

Multinational corporations not only have these differential standards in their supply chain but also when they produce the same products in different countries – such as the Coca Cola plant in Plachimada in Kerala. Villagers in the area in early 2000 noted that soon after the factory opened, their wells began to dry up and the available water turned toxic. In 2002, villagers began an impromptu protest at the factory gate which continued for years, gathering support and continued litigation finally led to the closure of the plant in 2004. Coca cola is one of the most ubiquitous symbol of globalisation, with factories across the world, but such instances of gross violation are only heard from their plants in the global south.

After years of negotiation, Union Carbide, responsible for the Bhopal tragedy paid a total sum of USD 470 million in 1989 for the over 500,000 people affected. In 2017, DuPont and Chemours Co. agreed to pay $671 million in cash to settle 3,350 claims (200,299 USD per person) involving a leak of a toxic chemical used by them to make Teflon in their West Virginia plant. The leak contaminated local water supplies and has been linked to six diseases, including cancers. If we did a back of the envelope calculation, 1 USD in 1984 = 2.36 USD in 2017 and thus 470 million USD in 1989 for 500,000 people meant 940 USD per person. Thus what we can clearly see is the price of life of a US citizen is over 200 times that of an Indian life!

The sheer scale of discrepancy in the cost of life is apparent from these two settlements even if the two settlements are separated by time.

The workplace standards in the global north are high as they value their own lives more and companies have to pay dearly if they are found to violate these standards. The justice system also puts high value on the cost of life. Consequently, companies move their production to countries in the global south where these standards do not exist or where they can arm twist the governments to lower their workplace standards.

This flight of capital/ investment is not just between countries but even within a country. For example, if the state of Tamil Nadu has a higher standard of safety requirement, allows lower permissible limit of hazardous chemicals, investors will threaten to shift production from the state to a state that has a more flexible standard. This coupled with the flexibility in the present code to allow states to change permissible limit of hazardous substances, makes it possible for investors to arm twist governments to change policy.

What can we do?

On 31 October a hundred years ago, the All India Trade Union Congress was founded. In this one century, workers have fought to secure their right to laws that protect their safety at work. How much these laws worked or how much they covered is not the issue in the present situation. The laws provided a framework that workers could legally fight for. In the rally of the founding congress of the AITUC, Lala Lajpat Rai, the newly elected president, stated that the goals of the trade union should be to Organize, Agitate, and Educate. That is where we are again as history repeates itself.