I feel sorry for the youthman today

The system is bad for the youthman today

Every day and every night they suffer

The youthman want to sleep but no place

The youthman want to eat but no food

The youthman want good dress but no good dress

The youthman want to buy but no money

The youthman want to work

If no work, how do you expect him to eat?

A 2008 song by a Sierra Leone hip hop artist Lansana Sheriff

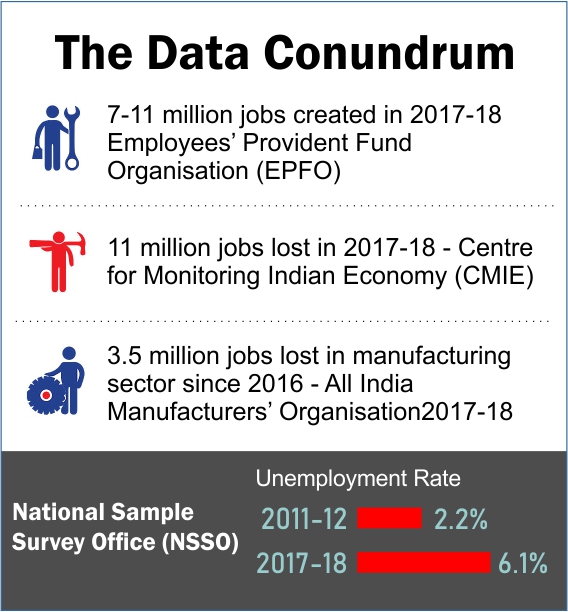

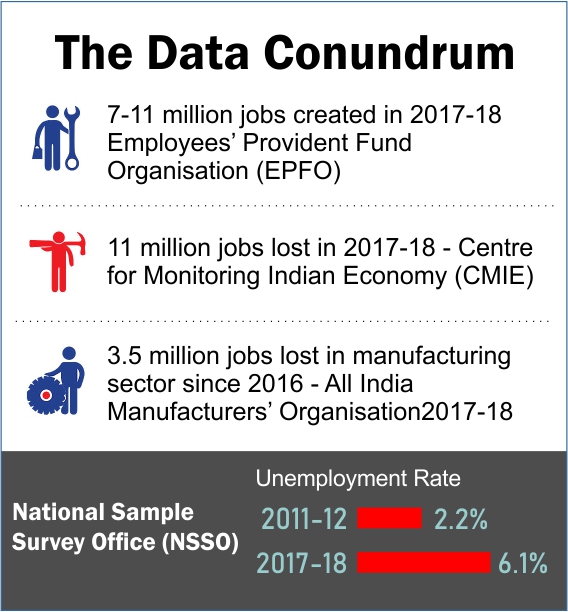

For the last two months, newspapers have been flooded with stories of government data on jobs being suppressed by the government itself. It all began with two members of the country’s National Statistical Commission, PC Mohanan and JV Meenakshi, resigning amid ‘disagreements’ with the government over the delay in the release of the latest Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) of the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO).

On 31 January, this report was leaked to a newspaper. It revealed that unemployment rate was at 6.5% – a rate not reached in 45 years! The data was even starker for the youth: unemployment rate among rural men in the 15-29 age group shot to 17.4% in 2017-18 from 5% in 2011-12. For women in the same category, unemployment stood at 13.6% in 2017-18 compared to 4.8% in 2011-12. The unemployment rate for the urban youth was even higher, 18.7% for men and 27.2% for women.

Government tried to deny and discredit the report while producing other data to prove creation of jobs.

What is this PLFS?

The Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) is prepared by the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO). It captures indicators on employment and covers categories including state, sex, socio-economic background, types of work, etc. It is a household survey and hence captures workers from all types of workplaces unlike other employment surveys that focus on enterprises and thus cover only formal and regulated workplaces. This survey report is for the period July 2017 to June 2018.

Why was this Report not released?

This Report by a government agency showed that the country is suffering a severe job crisis. This did not fit the story that the government wanted to put out. In fact in a press conference the NITI Aayog CEO, Amitabh Kant, claimed that India was creating adequate jobs for new entrants, but “probably we are not creating high quality jobs”. The NITI Aayog applied the “principle of authority” and stopped the release of this report. The reason cited for this intervention is that the PLFS is unscientific in design and not comparable with either the Employment Unemployment Surveys (EUS) of the NSSO conducted till 2011-12 or the EUS of the Labour Bureau conducted till 2015.

In reality, the PLFS was approved by the National Statistical Commission (NSC), as is the requirement for any NSSO report before its release. There has also been no change in the methodology between the earlier rounds of EUS and the PLFS.

The argument that unemployment could not have increased between 2011-12 and 2017-18 since people living in extreme poverty declined during this period is factually incorrect. Several reports have claimed that the number of people living in extreme poverty has declined in this period. The poverty reports are, however, not based on actual survey data, unlike the employment reports but on indicative projections. There has also been no survey based estimate of poverty since the census of 2011.

The government in contrast says that provident fund (PF) data shows that jobs are being created. Why is this being questioned? PF data is however not a good estimate of job creation. PF applies to establishments with 20 or more employees. When a business employing 19 employees hires one more worker the total number employed becomes 20 hence it then comes under PF. The business has only created one new job but 20 workers have come under PF. Also when contract workers are rotated every 90 days or 120 days from one establishment to another they may end up with a new PF account each time. This does not mean a new job has been created. Finally, the PF data provides numbers of new registrations. PF does not provide regularly updated data on how many existing accounts are inactive. As a result we do not get information on how many jobs with PF accounts are being lost each year. Hence we cannot rely on PF data as a measure of job creation.

Government says jobs are being created by new businesses being set up through loans given out under the Mudra Scheme. There is no data however for data of jobs being created under Mudra. What we do know is that 82 per cent of loans under Mudra are of a maximum of Rs. 50,000. Therefore the question really is how many jobs can be created with Rs. 50,000 if any at all.

Also the government says that there are jobs in the informal sector: as pakoda sellers, tea sellers, rickshaw drivers etc. These ‘jobs’ may indeed be created but nobody undertakes these tasks through their free will. If a tea seller makes Rs 200 after working for 12 hours a day she does not earn the minimum wage and does not have enough money to save for her old age or pay for her family’s healthcare needs. This “self-employment” is not out of choice but forced by economic reality of not being able to find a job. In employment data this work is not classified as “employment” but “under-employment”.

The issue about jobs data is not the end of the discussion. What the data does tell us is that in the last several years almost no jobs have been created and whatever jobs that have been created are low wage, unprotected and unregulated jobs.

The question we must ask is how did we get here? What is at the root of this crisis?

The Story of Jobs

The jobs crisis is over two decades old now. The structural changes in the economy brought forth in the 1990s changed how many jobs are created and what kinds of jobs are created.

India’s growth trajectory of the past two decades has been on the back of bad jobs. There has been no consistent focus on employment creation as a key constituent of economic policy. Policymakers have looked at every sector in isolation. When it comes to agriculture, the focus of policymakers is not on the extremely large number of agricultural workers and other rural workers dependent on agriculture. This has resulted in a huge surplus labour force for which there are no jobs. This army of surplus workers depresses wages both in rural and urban areas, as rural workers migrate to urban areas in search of jobs. In manufacturing and services, government has provided sops to businesses and companies for capital intensive investment. This framework put in place in the 1990s has with successive governments resulted in more contractualisation as government has allowed the implementation of labour law to be weakened. As a result companies and businesses are allowed to employ low paid and unprotected workers.

Between 1993-94 and 2011-12: the highest growth in job creation has been in the non-manufacturing casual labour category mainly in the construction industry. These jobs are entirely unregulated and unprotected. The second highest job creator is services: mostly in low end trade, transport and communications jobs. These jobs are divided between self-employment and wage employment. Jobs grew, but they were mostly low paid and unprotected.

2008 brought in the global financial crisis. Though India was not immediately affected by it, in the course of years that followed the job crisis deepened because of this impact.

The Crisis today

The government, in 2014, promised 2 crore jobs every year.

It said that if all labour laws were “rationalised” into 4 codes it would help create jobs since it would help “ease of doing business”. While these changes are still underway at the central level many of these changes have been brought about in states including Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, etc. At the center the government was able to change the rules to introduce fixed term employment. This took away the right of workers to seek regularization as under the Contract Labour Act. Further, the government introduced self-certification by employers which further weakened the implementation of labour laws.

Despite all these efforts of freeing businesses from regulatory requirements very few new jobs were created. The PLFS data clearly shows this. Hence there was no change in the structure of employment despite all the efforts of deregulation of labour laws.

In addition, government policies also resulted in job losses. According to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy-CMIE the move to demonetize currency notes of Rs.500 and Rs.1000 in November, 2016 resulted in the loss of 15 lakh jobs.

In 2017 the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax also put pressure on micro, small and even medium enterprises, leading to loss of 18 lakh jobs.

What now?

There is no escaping that there is a jobs crisis. It is also clear that long term government policy has contributed to this crisis and short term policy has aggravated it. Hence government must change its policies and if it doesn’t then it’s the task of workers and their trade unions to make the government do it.

Government has to relook at the minimum wage, at financial provisioning for the NREGA and other forms of social protection, at the efforts of deregulation of labour law and how counterproductive it has been and at developing manufacturing industry through self-reliance. These will all contribute to job creation.

The jobs crisis has led to unsustainable and undeliverable political demands of job reservation coming from all communities. We are also witnessing the growing crisis in rural areas. There is today restlessness among young people. This social and political turmoil can only be addressed if there are quality jobs for all.