… Now the man that invented the steam drill

Thought he was mighty fine

But John Henry made fifteen feet

The steam drill only made nine, Lord, Lord

The steam drill only made nine

John Henry hammered in the mountains

His hammer was striking fire

But he worked so hard, he broke his poor heart

He laid down his hammer and he died, Lord, Lord

He laid down his hammer and he died…

Excerpt from the African American folk song ‘John Henry’

This is a song about an African American construction worker cutting a tunnel through a mountain to lay a railway line sometime in the 1870s. The legend goes like this: the company building the railroad wanted to bring in a steam drill to replace the workers but John Henry challenged the company that he could drill more than the machine. And he did – he drilled fifteen feet and the steam drill could only drill nine. He won the challenge but lost his life. He lives on to inspire forever.

Every day we hear a new story about how Amazon has a robot that will deliver our orders to our doorstep, or how Suzuki and Volkswagen or Siemens already has robots on the shopfloor that perform tasks that were earlier performed by us, or how General Motors and Ford are planning huge job cuts of their white-collar workers. Every one of these stories are true. Every day we also read about jobless growth, about rising unemployment, of skill gaps that are making it difficult for workers to find jobs. We are simultaneously reading about the proposal of a universal basic income as a policy initiative to address this growing crisis. All these are being read in two possible ways: one, those reading are getting paranoid and are beginning to think that eventually all jobs or most jobs will go away and there will be no option left before working people but to survive on dole given away by our governments; and two, those reading this are also deciding to ignore it all and believe that this will not affect us in any way as our jobs are either too low end or too high end to be replaced by robots. These are also people thinking that our economy is far too less developed for any of this to reach us in the near future. The problem is that neither of these positions are totally true or totally false. Digitalisation, in the broadest possible sense, is a mix of both realities. While it is creating loss of jobs certainly in certain categories of employment, and these categories of employment are present across the world irrespective of their level of development, the spectre of digitalisation is far more amplified than what it can do in reality. This is also because much of the writing on the impact of digitalisation is technological predictions that somehow assumes away any form of resistance of people to this technological progress that will destroy their rights and pose a challenge to their very existence.

Is Digitalisation different from earlier technological changes?

A lot of us are primarily confused as to what is digitalisation. Many of us often confuse it with automation. But this is not the case. To put it very simply, digitalisation is the process of collecting and converting all information into digital data that can then be processed and analysed to feed back into the same system or other digital systems. So in the manufacturing industry, digitalisation often means that a system is put in place that collects and converts data from the shopfloor to then change how a production process works. For example, a simple biometric device installed at the gate and doors of a factory converts entry and exit data of workers and their movement on the shopfloor to analyse worker attendance, movement on the shopfloor and its need, leave and breaks taken, and so on. This can then also be used to streamline and rationalise the organisation of work and make it leaner by squeezing break times. And the difference that this process has with earlier forms of automation is that in this case this information processing is happening without human intervention and hence is devoid of an understanding that this change will affect the life of a human being and not the functioning of a machine. Thus this change is more ruthless.

In this context, it is worth remembering what David Ricardo had argued in 1821. He had stated that machines may “render the population redundant” but what we saw in the 1830s, was widespread worker protests and trade union activity reached a new level. For the first time in England workers began to organise trade associations with nationwide aims. In 1830, agricultural workers in southern and eastern England rose in protest against mechanisation in agriculture. It began with their destruction of threshing machines. In the years to come trade union membership kept on increasing and so did the power of unions. In the post-world war period, the power of trade unions pushed even governments to move towards a welfare state. In the 1990s, employers realised that large workplaces may increase productivity but it also provides the opportunity to workers to come together in large numbers for collective action against employers. Thus began the effort to break down production processes all over again. The post-Fordist models of production is all about breaking down each process into tiny fragments produced at centres spread across the world to increase profits and destroy the power of unions. The smaller the workplace, more isolated is the worker in it. More isolated the worker, the easier it is for employers to control her and more difficult it is for unions to organise her. Digitalisation is the newest improvisation towards this but its ramifications are far more challenging than the earlier innovations.

Some of the key challenges that digitalisation poses before us are:

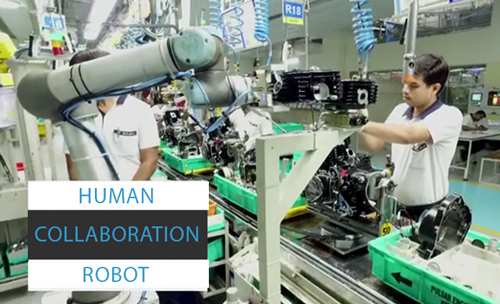

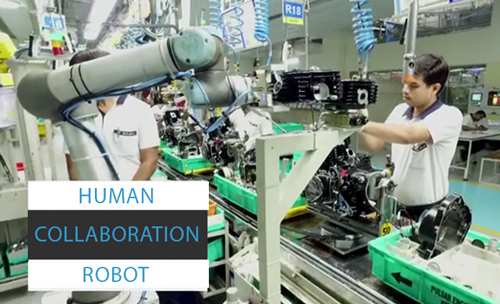

- •Job loss and Precarisation of work: Digitalisation will bring in robots or processes that will replace humans on the shopfloor.

E.g. The photo is that of a collaborative robot used at by Bajaj Auto Ltd. in its two wheeler plants at Chakan, Aurangabad and Pantnagar. The company has installed close to 120 robotic arms, which are termed collaborative robots or co-bots produced by Universal Robots, which are used to perform certain specific tasks that were of course earlier performed by workers. Bajaj claims that this has increased their productivity from 507 vehicles per person per year to 804 vehicles per person per year in 2016.

E.g. The photo is that of a collaborative robot used at by Bajaj Auto Ltd. in its two wheeler plants at Chakan, Aurangabad and Pantnagar. The company has installed close to 120 robotic arms, which are termed collaborative robots or co-bots produced by Universal Robots, which are used to perform certain specific tasks that were of course earlier performed by workers. Bajaj claims that this has increased their productivity from 507 vehicles per person per year to 804 vehicles per person per year in 2016.

The Chakan and the Pantnagar plants of Bajaj saw militant workers struggle from 2013 onwards. Most of the workers were young and large number of them were on precarious contracts. The Bajaj management was adamant. They refused to bargain in good faith with the union representing all workers. They even claimed that the union did not enjoy the support of the workers despite the fact that they struck work for 50 days in a row. Thus, it is not surprising that this management brought in the co-bots in 2016 just before the renewal of the wage agreement at Chakan to create an atmosphere of threat and fear among the workers. An average of 40 co-bots per plant will not replace all workers but it certainly creates enough fear amongst those remaining that they may lose their jobs too. It also creates enough fear to reign in any future protests. And it also creates enough fear to make workers work much more in the fear of being replaced. Thus even if the loss of jobs is not substantial, the fear of this loss is more than substantial. Simultaneously, the increase of productivity may be real but to attribute it entirely to the co-bots is not real. Productivity on the shopfloor also increases due to this heightened sense of fear and insecurity among workers.

- •Change in Work Organisation and Increased Control at work: Digitalisation increases monitoring and control over workers whether at the workplace or even remotely.

Eg. In the last few years the courier or the delivery worker at our doorstep has started coming with a tablet on which we are supposed to sign off when we receive a package. Similarly, sales representatives today across the world are equipped with tablets to record their progress during the day. The tablets were introduced to increase their productivity and shorten sales cycles. Despite the fact that many sales representatives were paid based on their achievement of certain sales targets, the new device pushes workers to also run against time to achieve these targets thereby increasing their work intensity and increasing the monitoring of their work at every point of the day. This has led to increased stress at work. It has also led to an increase in the number of road accidents of sales representatives or delivery workers on two wheelers trying to keep up with the targets. The road accident statistics in urban centres do not however correlate it to these targets. Thus data created is used only by employers while there is a lot of data available that is not used by us.

Additionally in the case of a sales representative, the tablet reduces the need for a skilled worker. The knowledge of the product that an individual sales worker was supposed to have which determined his capacity to sell a certain product is no longer required. All the information is standardised and made available on the tablet. This takes away the need for a skilled worker and lowers the value of the work and hence pay.

- •Loss of Control over Data: Workers as workers and as citizens become providers of a lot of information about themselves, their choices and their vulnerabilities to various agencies, be it employers or others. Once this data is provided the individuals no longer have any right over how this information that has been gathered about them is used. It may even be used against them without their consent.

E.g. This is a Fitbit that is provided to many employees by their HR department, often as a gift, to help employees monitor their own health. This gesture looks like a gift that shows a genuine concern for the health of employees and is provided to ‘motivate’ employees towards their own individual fitness goals. A Fitbit can be used to accurately track movement based fitness of the user. Fitbit, when it provides its devices to a certain company for its employees, also trains its HR managers on how to use the administrator platform, which gives them access to aggregate data around the health progress of employees.

E.g. This is a Fitbit that is provided to many employees by their HR department, often as a gift, to help employees monitor their own health. This gesture looks like a gift that shows a genuine concern for the health of employees and is provided to ‘motivate’ employees towards their own individual fitness goals. A Fitbit can be used to accurately track movement based fitness of the user. Fitbit, when it provides its devices to a certain company for its employees, also trains its HR managers on how to use the administrator platform, which gives them access to aggregate data around the health progress of employees.

This data on how the employee leads her life, how much she exercises to remain fit, are now available to the HR department of the company. When a worker in this company now falls ill, especially affected by work-related stress, the HR can use this personal data to show her that she fell ill because she did not adequately take care of herself and thus hold her responsible for her ill health. Thus a collapse of an employee’s health is no longer the responsibility of the employer who causes it, but becomes the responsibility of the employee herself for not taking care of herself. What this evades is the simple fact that she may not have had the time to take care of herself. She worked long hours, or worked extremely intensively for a certain period of her day which exhausted her, and then of course she had to also come home and take care of her home, or work part time on a different job to make ends meet. Thus data gathered is only used selectively to suit the purpose of the employer. What this also means is that with the Fitbit on her wrist, the employer employee relation does not end at the workplace. There is a monitoring mechanism attached to her 24×7 that keeps providing information about her life to her employer without her knowledge or consent.

To take this example one step further, let us assume that you are not given this Fitbit by your employer but you buy it with your own money to monitor your own fitness. There is no employer trying to control your life through your health data. But even then your health data is not secure. This is because Fitbit stores its data in a cloud. Recently Google has offered to provide Fitbit users with an online space to store their data. This generosity implies Google will now have access to this data and can sell this data to others who can then use this data to profile you as a consumer and sooner or later you will be offered various goods and services that you will be told is good for you.

Moreover, most of these products like the e-book Kindle, the Fitbit or the Amazon echo in the room, do not give you a real choice to protect your data from snooping or abuse by other apps. If you choose not to use their cloud based storage services or log-in using your account the product is, in most cases unusable or performs extremely poorly.

- •Disturbs Work-Life Balance: This sounds a bit extreme in our country where the largest majority of workers have no work-life balance as they struggle to make both ends meet. However, the mobile phone is the greatest intruder in our lives. From a domestic worker being called on her mobile phone by her employer to check if she is coming to work or changing her hours of work to the office executive who has to attend to work phone calls and emails through the day and even possibly at night. The working hours are no longer restricted to the hours the worker is present at work. It eats into family time, into rest time, into holiday time.

•Not on Policy agenda: There is no clarity on the issue of Digitalisation and no concern for its impact yet among policymakers. The issue is discussed in business circles as a way forward but there is no discussion on its impact on workers or even citizens. Unfortunately, this is also not on the collective bargaining agenda of trade unions. The vast variation within the country and the large number of workers in the informal economy along with those unemployed makes it difficult for unions to even understand the issue clearly.

Is this the Beginning of the End?

Very unlikely. The problem with those who believe that this is the beginning of the end is that they discount the capacity of workers to understand changes and how it affects them, they also discount the capacity of workers to come together and take collective action against changes that adversely affect them, and they also discount the fact that this will not be the first time that workers may do so. The assumption is that technology progresses in its own trajectory and there will not be any resistance to it from any quarter. The problem is that in a capitalist world, it is not just workers who resist a certain trajectory of technological innovation but even competing companies resist each other and create barriers in the path. The predictions of job loss due to digitalisation is all based on the assumption that there shall be no resistance.

Resistance builds whenever there is oppression and the challenge before trade unions today is how to bring this resistance together, how to provide it direction and how to sustain it to build sufficient power to resist this stage of industrial development.

We started this piece with the story of John Henry who stood alone against the powerful steam drill and defeated it on his own. However, he died too in resisting the power of the steam drill because he was alone. Changes have happened through history however not with individual actions but when individuals come together to take collective action.