Self-employment is the buzz word today across the world. From the ubiquitous tea vendor on the street to persons providing various services through online portals, including couriers, taxis, food and grocery delivery, to home based workers in the beedi, papad and even garment industry are all considered self-employed. Two third of India’s 98% informal workers are self-employed.

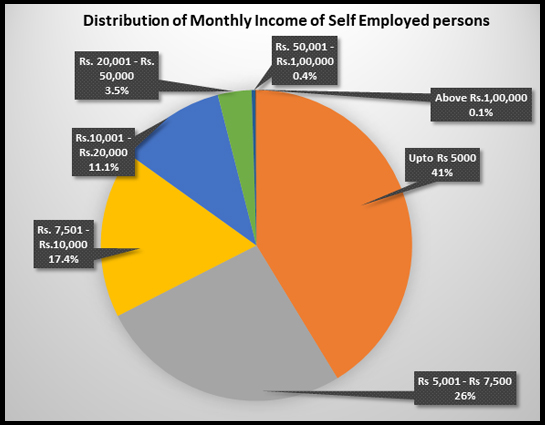

According to the Report of the Fifth Annual Employment-Unemployment Survey, 2016, of all persons engaged in the labour force, 46.6% were self-employed. If we look more closely into the self-employed category we find that more than 40% of self-employed persons have a monthly income less than Rs. 5000, and while more than 84% of self-employed persons earn less than Rs. 10,000 per month. These are our small and marginal farmers, street vendors, delivery workers, beedi workers, papad makers, home based garment workers, etc. with large number of them being women. International financial institutions since the 1990s have been aggressively advocating for this kind of ‘entrepreneurship’ of people as a solution for the unemployment and underemployment crisis in the global south. By dictionary definition, an entrepreneur is a person who sets up a business or businesses, taking on financial risks with the expectation of profit. But the disproportionate number of ‘entrepreneurs’ among the poor makes little sense. The poor have little or no capital of their own, almost no access to credit, and they don’t seem to be even making enough money to survive. Then why do the poor become entrepreneurs in our country and elsewhere too? They are self-employed not by choice but are self-employed because there are no jobs. According to some estimates about 12 million young people are set to enter the workforce every year over the next two decades and according to none other than the World Bank, India must create 8.1 million jobs a year to maintain its employment rate. The CMIE-BSE survey results show that employment has actually declined in the period January-April 2018 to 405 million as opposed to 401.7 million in January-April 2017.

Are you a Worker or an Entrepreneur?

Coming back to the reluctant self-employed, we can divide them into two distinct categories: first, those who are definitely workers as defined by law and misrepresented as ‘self-employed’ and second, those who actually run a business on a very small scale, using mostly family labour, such as a street vendor, and located in the bracket of that 84% making barely Rs.10,000 a month.

According to the Industrial Disputes Act, 1948 and subsequent rulings of the Supreme Court expanding the definition, there are a few broad criteria that qualify a worker as a ‘workman’.

One, Who has Control: A workman under the Industrial Disputes Act must be under the supervision, direction and control of their employer. A workman thus must not have the power to supervise, grant leave, initiate disciplinary actions against, conduct performance appraisals or hire or fire any other employee; or influence business decisions of the establishment.

And two, What work do you do: It does not matter what designation is given to a worker, what matters is the main tasks that they perform at their workplace. If the main or substantial task for which a worker is employed is that of a ‘workman’ then designation or any incidental work done will not take the worker outside the purview of the ID Act.

So using these two broad parameters, we shall look at the following persons and classify them as workmen or not.

A home-based beedi worker or a garment worker is often termed as self-employed ‘entrepreneur’ because she buys her raw material from someone, works on it and then sells it in the market at a mark-up. While on the face of things this is true, if we look closely, she is provided raw material by a fixed supplier, she is told how to produce, what to produce and in what quantity by the contractor, and she sells it back to the same contractor at a pre-fixed price. She is not free to buy her material from anywhere she wishes to. She is not free to sell what she produced to anybody she wishes to. She is not even free to produce as much as she wishes to. The size, the design, the quantity are all controlled by the contractor. In fact, it is not even the contractor who decides this. It is the final buyer of the products the worker produces who decides and controls all this. Although the worker may not know in many cases who they produce for, it is finally the owner of the company who sells the product who makes all the decisions. Thus, to many it may seem that the beedi or the garment worker is engaged in a business relation where she makes the decisions, in reality it is the buyer company that is responsible. The buyer company may be an enterprise that is located in our own country as in the case of a beedi manufacturer or may even be a Multinational garment company sourcing its products from across the world. The home-based worker is a necessary element of the supply chain of the company. Hence the beedi or the garment worker whether accepted by the company as a ‘workman’ or not, is a workman under the ID Act and is definitely not self-employed.

Moving to a different location and spectrum, we all have seen advertisements in newspapers calling for people to apply as a home-based data entry operator and earn several thousand rupees a month. A lot of young people apply for these positions in urban areas. Are these data entry operators self-employed? Most of the time the persons so employed tell us that they work at their own pace, decide how much work they do and work when they want and don’t work when they don’t want to. That gives the impression that this person is free to do what she wants and when and how. However, once again, this is not entirely true. The work is strictly monitored, targets are fixed and the pay is piece rated and hence productivity linked. Thus the control of how much one works or not is determined by the entity that provides the work. Even if not visible, this entity decides and controls whether work should be given to this person, how she works, when she works and how much she works remotely through the pay structure. Visibility or in this case invisibility of an employer does not ‘blur’ the employment relation. The employment relation exists and if invisible it needs to be established, not given up.

The much debated issue today across the world is whether an Ola/ Uber driver is an ‘independent contractor’/ ‘business partner’ or a workman. Uber today is fighting in employment tribunals across the world to establish that the driver-owners are independent contractors/ business partners while the driver-owners have successfully established that they have a clear employer-employee relation with Uber. This is being challenged by Uber in courts of law as their entire profit model is based on this misrepresentation of reality. And this is not just for online taxi services such as Uber/Ola, it is also true for plumbers and electricians being provided by UrbanClap, or food being delivered by Swiggy and municipal safai workers in states like Uttar Pradesh. The Government of India has signed a MoU with UrbanClap to provide work to skilled workers from their Skill India programme. The argument placed before the London Employment Tribunal by the Uber drivers through their trade union is that the allocation of work to a driver, the determination of route to be taken, the number of rides to be given, the pay and disciplinary action is all controlled by Uber and thus the employment contract as ‘independent contractors’ is a bogus contract. The fact that many drivers and such other workers in India continue to believe that they can stop working by simply switching off their device is again only an illusion. If this is done repeatedly and at the will of a worker, the company retaliates by taking punitive action by providing less work and hence less earning which then forces workers to follow the discipline of the device thereby establishing their control over the work relation.

And finally let us examine the much celebrated ‘chaiwalla’ or the ‘pakodawalla’ or our familiar ‘thelawalla’ selling vegetables in our locality, be it urban or rural. The number of people dependent on such livelihoods is very high in our country and is growing too. Development perceived as a process of transition from informal relations to a ‘modern’ state with formal contracts, has moved backwards. The existence and profitability of existing businesses in the globalised world is intrinsically linked to the existence of this informal economy. There is no compartmentalised informal and formal today. The formal exists and owes its stability to the existence and instability of the informal.

On one hand, let us consider a contract worker in a multinational pharma or engineering company living in the city of Pune or even in Baddi in Himachal Pradesh. He is able to survive at the minimum wage because he buys his vegetables from the local thelawala, eats his tiffin at the chaiwalla next to his factory gate and buys his clothes from the local weekly bazaar. Also at each buy, he tries to bargain down the price to suit his pocket. This informal market ensures his survival. Now in this relation, let us consider the chaiwalla, or the thelawalla. His work relation differs from the contract worker. The chaiwalla has to pay rent or protection money (hafta) for putting his stall where he is, whether legally or extra-legally, in every transaction he also has to bargain to retain his price, sometimes he wins sometimes he doesn’t but he accepts it to retain his client, and finally he has to pay for the labour that he (and in some cases other members of family) put during the day. What therefore happens in reality is that after paying off the rent and covering the costs of production, if the chaiwalla is able to make some earning, he sees that as his profit. Thus if the rent per day is Rs. 100, the cost of tea, milk, sugar and fuel is Rs. 500, and the chaiwalla makes Rs. 700 in a day, he thinks this Rs. 100 is his profit. But this is not his profit. He has ignored the fact that he has worked for more than 8 hours in the day for which he has not paid himself a wage. If he had to pay a worker at this establishment at the minimum wage, he would have to pay Rs. 300 but since he hired no one he did not have to pay. Hence this mode of production allows for intensive exploitation of the entire family (sometimes even child labour) at sites where the state does not intervene. Here the surplus is extracted through more than just the wage-profit route as in the case of wage labour. This person is not an entrepreneur and neither is he wage labour. In fact he is engaged in self-exploitation to subsidise the formal sector. And if we now go back to the fact that more than 84% of the self-employed in our country earn less than Rs.10,000 things start making sense. Through self-employment employers at the end of the supply chain are able to extract much more than even through wage labour. Keeping a large section of people in the self-employment trap is essential to extracting profit beyond what is possible through a wage-profit route.

The largely elite argument that people choose self-employment as it provides flexibility, autonomy and allows a work life balance may have some element of truth for the top 1% of the self-employed but definitely not for this 84% of the self-employed. They would happily give up being an ‘entrepreneur’ and would like to have a job with a stable wage, social security, with weekly off, annual pay, maternity leave and other benefits. These ‘entrepreneurs’ are among the over 280 lakh persons who applied at the Indian Railways for the 90,000 vacancies this year.