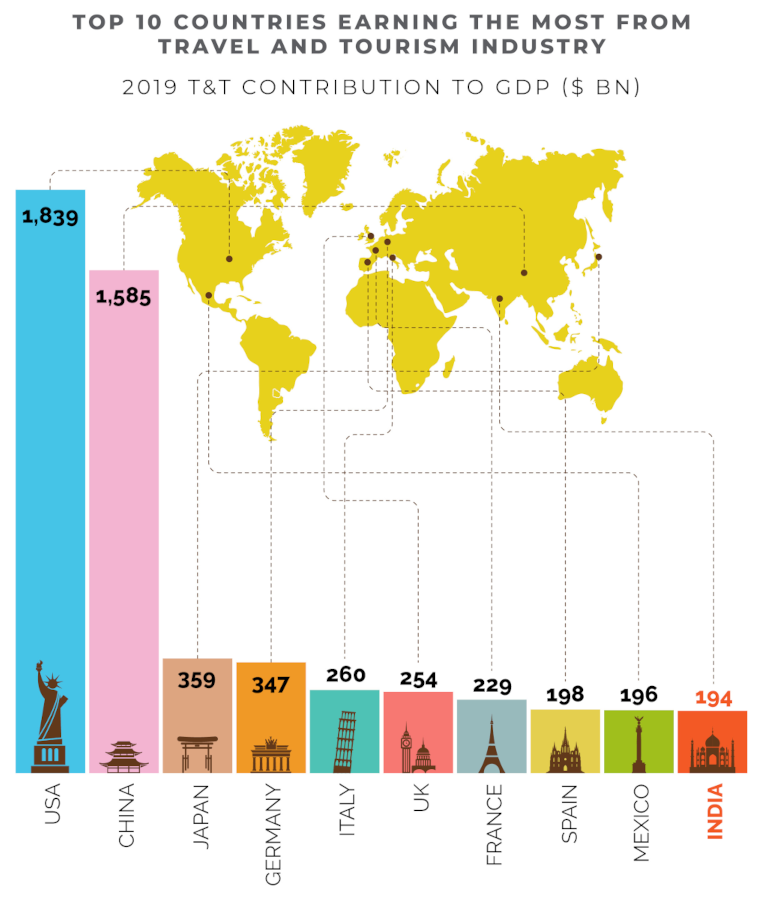

The travel and tourism industry accounted for 10.3% of the global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2019, amounting to $8.9 trillion. Every fourth job in the last five years was in this sector, which employed more than 330 million people directly or indirectly employed in the sector till 2019. It was the world’s third-largest export industry after chemicals and fuels — ahead of automotive products and food.

The tourism industry was looking forward to a bumper 2020: Major sporting challenges, including the Tokyo Olympics, and cultural events such as Expo 2020 Dubai were on the cards. But then COVID-19 struck the planet; by May 2020 almost all countries imposed partial or full lockdown with strict restriction on movements.

Tourism, which relies on the same human mobility that spreads the disease, was subjected to the most stringent and lasting restrictions and suffered more than any other economic activity: The United Nations World Tourism Organisation estimated on 7 May, 2020 that earnings from international tourism might have shrinked 80% from 2019 and 120 million jobs could be lost.

By end-May 2020, the novel coronavirus had begun to plague the travel industry: The top 20 airlines of the world reported an over-90% dip in passenger frequency. Hotels remained vacant while cruise ships were the worst hit. In early February 2020, cruise ship Diamond Princess made headlines as over 700 people aboard contracted the virus; ultimately 14 people succumbed to the disease. Over 100 cruise ships and 70,000 crew members remained stranded around United States waters alone as the country’s Department of Disease Control denied them entry.

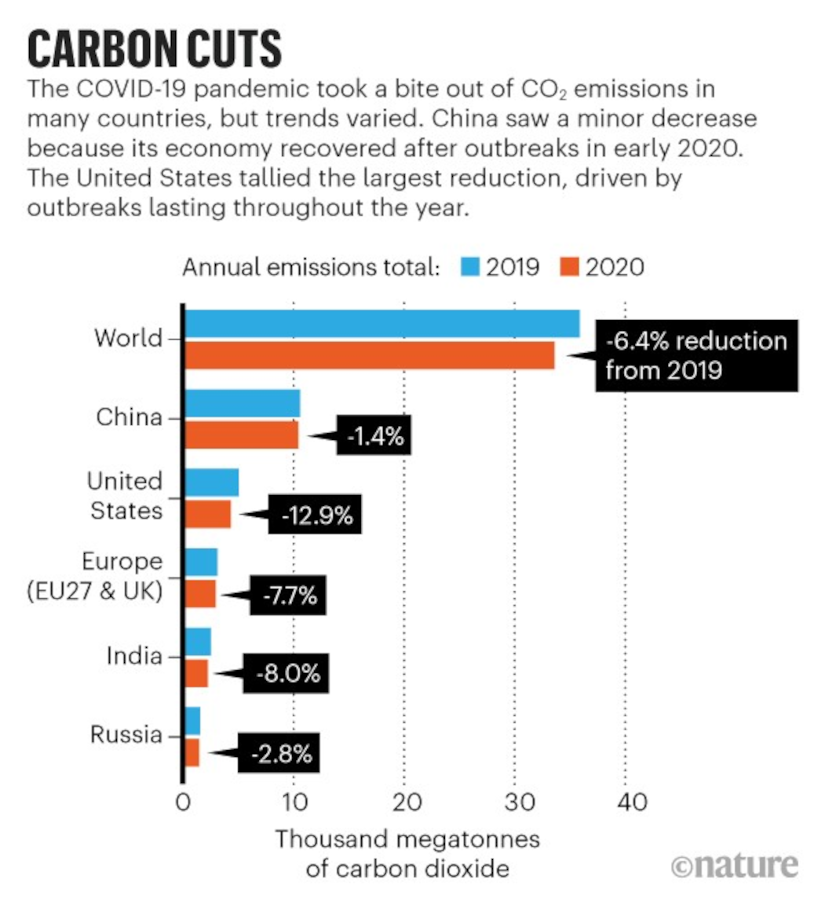

As brakes were applied to all human economic and social activities due to COVID-19 our planet got to breathe. After rising steadily for decades, global carbon dioxide emissions fell by 6.4%, or 2.3 billion tonnes, in 2020. Amid death and sorrow, people saw clear skies in some of the most polluted cities across the world, including New Delhi as smog gave way to clouds. Several photos of birds and animals rare to spot in the cityscape did the rounds on social media websites.

This was short lived. As COVID cases started to decline, countries eased lockdowns and activities started picking up, including in the travel and tourism industry. Recently, two news images have been doing the rounds: One of Manali — a small hill town in northern India —overcrowded with tourists without masks, violating all pandemic-related protocols. Another is from the USA where employers in the tourism and hospitality industry complain of a dearth of workers. The two stories from different continents, miles apart, sum up all that is wrong with travel and tourism today.

The environmental cost of tourism

First, let us consider the case of Manali that has drawn the ire of netizens. For it is no different than what happened in Venice in 1989 when over 200,000 people flocked to the city to listen to famous rock band Pink Floyd. They left behind the stench of urine and streets strewn with empty alcohol bottles and cigarette butts, which had a long-term effect on the city life. Or, the impact on the Yamuna flood plains in New Delhi of godman Ravishankar’s three-day-long World Cultural Festival in 2016; it was attended by over 3500,000 people, causing irreparable damage to the floodplain.

The problem here is not the tourists but the overall profit-driven market model that promotes tourism in certain places. The jobs in this industry are exploitative, monotonous, draining and isolating.

The idea of travel sold is of ‘taking a break’ for rejuvenation: One is supposed to shed all ‘workload’, responsibilities and be carefree on a vacation. Such vacations, however, are meticulously planned, often micro-managed by tour operators so much so that they are devoid of any sense of adventure or exploration — unlike the old times when travel was difficult, required grit and quite often ended up being dangerous. Current ‘#wonderlust’, social-media-fuelled travel is driven by big capital ensuring that there would be no danger or difficulty if you can afford it.

For instance, consider the toughest peak to summit — Mount Everest — which remained unconquered till 1953. In 2019, there was a traffic jam on the way to the summit as over 300 climbers waited for their turn to summit the peak. The reason: Tour operators who sold the idea that a three-day window in May would be the best to climb. The environmental cost of that jam is unfathomable. Everest Summiteers Association in 2011 collected 1.5 tonnes of garbage, including oxygen cylinders, ice pitons and scraps. This had to be flown to Kathmandu in helicopters.

No place is equipped to handle the environmental impact of such high footfall. Tourism advertisements, however, promise the best of the place in terms of weather, views and experiences devoid of the nuisance that the locals have to bear who inhabit the place. The person paying for the tour therefore feels entitled to exploit the resources for the promised ‘out-of-the-world experience’ because it’s an escape from their own exploitative work environment.

Most people like to believe that this is only true for the poor, ‘budget travellers’ — as the tourism industry likes to call them. Indeed, the rich harm more: Consider the following chart, showing carbon footprints for destination countries per person in 2013 for international (blue) and domestic (yellow) holidays.

The myth of trickle down effect?

At this juncture one may want to throw in the travel and tourism industry’s favourite ‘trickle-down’ argument. When the rich travellers spend it helps the local economy grow, creates jobs for locals and helps in preservation of travel destinations which are otherwise being ruined by the local population eg, ecologically sensitive areas. The hole in this argument is big enough to let the largest cruise ship and jumbo jet pass together.

First of all, the largest share of travel expenditure is towards long-distance air, rail, land or water travel. The rich definitely pay for the most expensive luxurious packages but the money is pocketed by airline or cruise companies. This money does not land-up in the destination country. In fact, the world’s top three cruise companies — Carnival, Royal Caribbean and Norwegian — are incorporated in tax havens with benign environmental and labour laws: Panama, Liberia and Bermuda respectively.

This is not an anomaly but the norm in travel business. Tour operators are incorporated in tax havens where they enjoy low taxes and avoid ‘irksome’ labour legislation while continuing to pollute our air and water bodies.

The second major expenditure is accommodation. This again is pocketed by corporate hotel chains infamous for exploitative work environment and non-payment of even minimum wages. In 2018, around 8,000 workers at 23 properties run by Marriott Hotels across the US went on strike demanding better pay and working conditions.

This explains the second news piece regarding the dearth of workers willing to work in hospitality and tourism industry. Travel and tourism does create jobs, but of what kind? These jobs are mostly in the unorganised sector with meagre wages and no health benefit or social security. For example, the rack rent for a Maharaja Room with a view of the Taj Mahal in Agra, India can range between Rs. 8,000 and Rs. 20,000 per night. The monthly wage of a worker there tends to be at the lower end of the rack rent.

Wage suppression is a norm in the hospitality industry defended with the argument that workers will make up for the deficit in tips. There are two problems with this approach. First, it shifts the responsibility of paying the worker a decent wage from the employer to the customer and rides on the guilt or large-heartedness of the latter. Second, it dehumanises the worker who at all times must please the customer to receive alms. Irrespective of the effort put in the task there is no surety of a stable income for the worker as wages are dependent on arbitrary factors such as the tipping capacity of the customer, the general mood or inclination of the customer to tip at that instance. It is no wonder then that workers do not want to get back to the old, rotten work culture in the tourism and hospitality industry.

Most other people who would come in contact with the tourist — a local guide or interpreter, taxi driver or shopkeeper would be self-employed and get no share in the money spent over travel or accommodation.

It is the same for cruise and airline operators, who digest large sums of money in either bailout packages or easy, interest-free loans without fulfilling any obligation towards cutting down on pollution or ensuring a decent working environment for their workforce. All major airlines in the Europe and the US benefited from the pandemic. They got to lay off workers en masse only to hire them back on sham contracts at considerably slashed wages and retain their profits. Furthermore, citing hardships due to lockdown, employers have lobbied hard for tax breaks and easing off of compliance to environmental and labour norms. Unsurprisingly big capital has succeeded.

A March 2021 research brief on ‘Sustaining tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic’ for the members of Lok Sabha propose:

- Relief from regulatory compliances

- Relief from penal provisions for delays in clearing dues

- Relief from excise duties

- Relief from electricity tariff

- Relief from property tax

And these companies didn’t even blink before forcing their workers to go on unpaid leaves and / or terminating their services amid the pandemic.

Third, tourism is a peculiar industry; it sells things that do not belong to it — the view of a monument, a hike, an under-water dive, the sighting of a rare animal, etc. Hence, it makes no business sense for the companies to invest in their preservation. The rarer the experience, the higher the price. Such firms hunt for rarer places, deplete them and move on when profits dwindle. While doing so, they often raise the prices of basic commodities, making them unaffordable for the local community.

The travel and tourism industry as it existed before the pandemic was parasitic, exploitative and insensitive not only towards the people it employed but the people it catered to. It must be held accountable for the depletion and pollution of common resources and exploitation of people who rely on it for their livelihood before it slips into its pre-pandemic normal.