Come gather ’round, people

Wherever you roam

And admit that the waters

Around you have grown

And accept it that soon

You’ll be drenched to the bone

If your time to you is worth savin’

And you better start swimmin’

Or you’ll sink like a stone

For the times they are a-changin’

This song of hope was written in 1964 by Bob Dylan – sixty years later it still reminds us that even if the troubles around us rise and attempt to drown us, we can still learn to swim and not sink like a stone in this changing time.

The pandemic has been used by employers across the world to push their restructuring agenda within their establishments and in policymaking. This has turned out to be an opportunity for big capital to wipe up smaller businesses and consolidate their power and establish their control over the market. Job losses are seen just as a ‘collateral damage’ in this restructuring. The faces of the people who lose these jobs, the faces of their children, other dependents do not matter to the people making these decisions. In a very different situation one of our political leaders had once said: When a big tree falls, the earth shakes. The pain of working people losing jobs, their children being forced out of schools, their ageing parents being denied medical care is this ‘shaking earth’ – soon all will be forgotten and the world will readjust and move on. This is actually true as every person readjusts to a new reality, willingly or not, and life goes on but the pain of losing a life, a hope does not go away.

Changing laws, Changing values

Let us start from the basis of all laws in this country – the constitution. The constitution of this country establishes constitutional supremacy and not parliamentary supremacy. The constitution declares India a sovereign, socialist, secular, democratic republic, assuring its citizens justice, equality and liberty, and endeavours to promote fraternity. The Fundamental Rights that are justiciable in courts of law and the Directive Principles of State Policy in the constitution create the benchmark for the labour laws in the country. Equality before the law (Article 14) is interpreted as “Equal pay for Equal work” in labour law. In the case of Randhir Singh vs Union of India, the Supreme Court said that “Even though the principle of ‘Equal pay for Equal work’ is not defined in the Constitution of India, it is a goal which is to be achieved through Article 14,16 and 39 (c) of the Constitution of India.

Starting from the Factories Act and the Minimum Wages Act, both enacted in 1948, soon after independence, the laws that have regulated labour and have been enacted till the 1970s aspired to establish a more equal, more just society where every worker would have the freedom to express their views without fear. The pre-independence Trade Union Act guaranteed immunity to workers’ representatives and protected the right to freedom of association of workers and the Industrial Disputes Act protected workers from unfair labour practices of employers and provided a right to raise disputes against violations of law by employers. These were laws that were meant to attempt to correct the existing imbalance of power between workers and employers. The right to form and join trade unions was considered inviolate which did not come with conditions. Article 19 (1) (c) of the Constitution guarantees citizens to form a union or association. The Trade Union Act works through this Article of the Constitution and the dilution of the provisions of this act is a violation of Article 19. But over the last several years this law has been diluted by bringing in amendments to make it more and more difficult for workers to form and join unions of their choice. Thus these amendments have diverged from the core value of the constitution for ensuring justice, equality and liberty. The existing imbalance of power is provided legitimacy by government and institutionalised. Even the legal pretence to create a balance is discarded.

From constitutional supremacy, we have now moved to the supremacy of one political ideology, bypassing even the parliament. Laws are being amended through ordinances assented to by the President or the Governor in advance as state legislatures are not in session and cannot be so in a while till the pandemic situation normalises. Thus the pandemic has provided not just the employers to consolidate their power, but also for the central government, and those state governments that are aligned with the central government, to consolidate and concentrate their power without any opposition within the parliamentary structure.

And finally, these amendments not just violate the basic principles laid out by our Constitution; these also violate international covenants that India is signatory to, especially those that violate the ILO conventions and the UN Declaration on Human Rights.

State Amendments to Labour Laws

The amendments that have been passed till date can be classified into three broad categories:

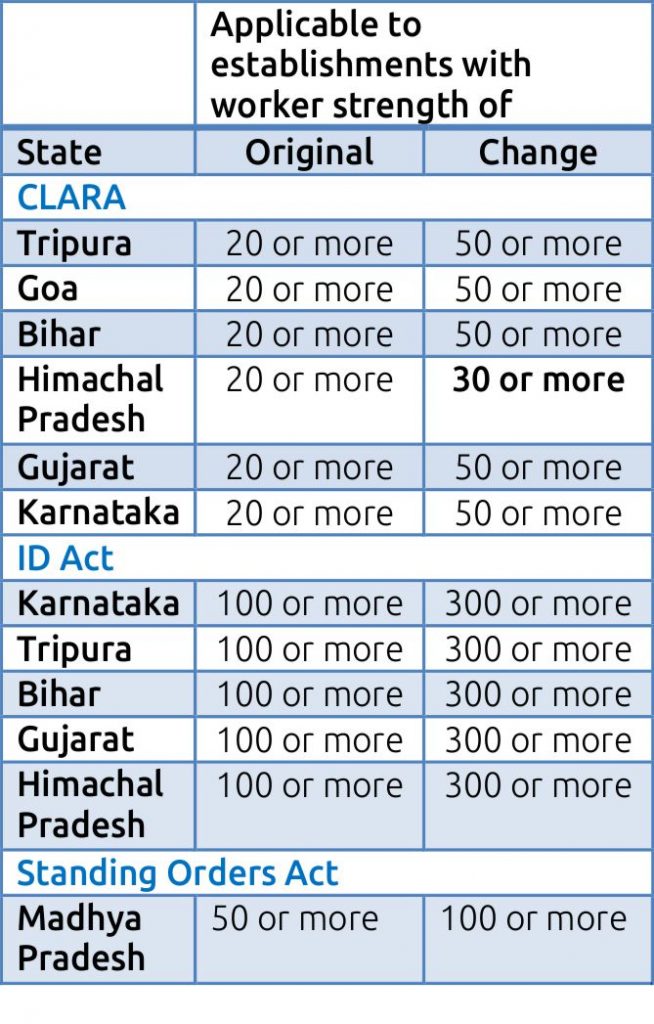

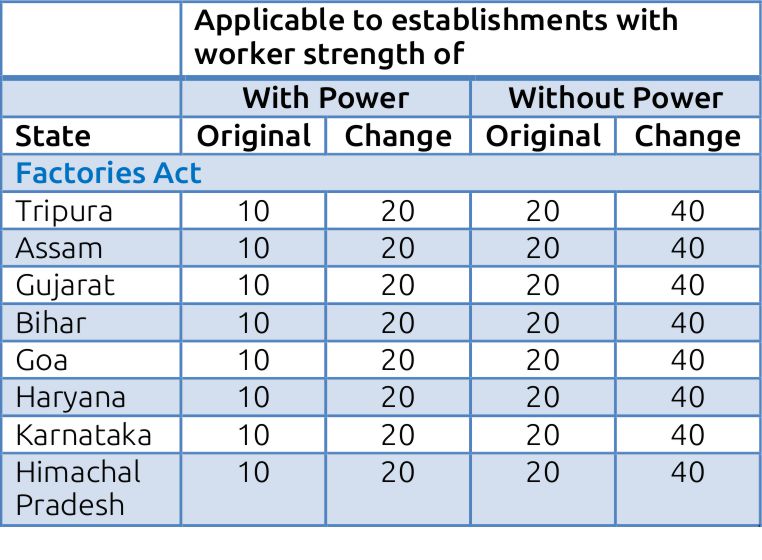

- Amendments that change the parameter of applicability of a certain law thereby taking a large section of employers out of the regulatory ambit of that law.

- Amendments that alter working condition

- Amendments reducing punitive action against employers

- Amendments to Applicability Clause

This form of amendment is a clever way of avoiding international repercussion and of violation of the constitution. What this form of amendment allows is keeping the law in its current form untouched and hence not in violation of any constitutional principle and yet taking away the largest section of the workers out of its regulatory framework. Thus by increasing the applicability, the government is free from the blame that it changed rights of workers guaranteed under a certain law and yet they are able to assure employers that most workers shall be out of its ambit.

As stressed incessantly by all, 93% of India’s working population is outside the regulatory framework. Increasing the applicability will now increase this already very large number (93%) further. This of course means that this huge section of the workforce will neither have security nor safety at work. But if we think that the remaining small so called ‘privileged’ section of the workforce will have an easy life is also not true. They will have to constantly live in fear that they will be replaced in their jobs by those who are willing to work more, willing to work under unsafe conditions, willing to work for less and this will push them to compete with the precarious workers to preserve their jobs. Thus protected or not, every worker will be pushed to a higher level of intensity at work under precarious conditions.

- Amendments in working condition

These amendments are straightforward and unpretentious – they are clearly aimed at making workers work more and under precarious conditions to ensure employers make more profit. There is no attempt to hide this intention. Government, both at the centre and these states, has decided that workers must pay for the losses their employers perceivably incurred due to the pandemic. Most employers across the country violated the 29 March order of the ministry of Home Affairs with impunity that directed all employers to pay full wages to all their employees and to not terminate them. Even the government did not defend it in the Supreme Court. Thus wage cost during the pandemic has been saved by most employers and yet both the employers and the government is convinced that workers must pay for the pandemic.

- Hours of Work

The most critical and the most debated one is the one on the extension of the normal working hours in a day. The over 150 year right to an eight hour workday is once again under legal challenge. For many years now, a large section of workers who have been outside the realm of the regulatory framework have worked longer hours but legally this has been an inviolate right. India, in fact, was one of the first countries to ratify the ILO convention C001 on hours of work in 1921.

States such as Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat and Tripura extended the maximum working hours in a day from 8 hours to 12 hours with the additional hours of work paid on a pro rata basis, i.e. if Rs 100 is paid for 8 hours, Rs 50 will be paid for the additional 4 hours, as opposed to Rs. 100 if the overtime rate had been applicable. The notification for UP however was withdrawn later. So under these notifications, overtime rate would only apply if workers beyond 12 hours of work in a day. This is a clear violation of the ILO Convention, C001.

States such as Rajasthan, Punjab, Madhya Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Goa (total number of OT hours in a week not to exceed 60 hours), Assam (also applicable for all S&Es), and Odisha have passed amendments changing maximum hours of work permissible in a day for a worker from 8 hours to 12 hours, with the exception of Karnataka that increased it from 8 to 10 hours. These were states that increased the maximum permissible working hours but with overtime pay for the additional 4 hours of work. In the case of Rajasthan and Karnataka, the states had to withdraw the orders under pressure from trade unions and in Punjab it was meant to be applicable for 3 months and therefore has expired now. These states increased the working hours but by continuing to pay a double wage rate for the additional 4 hours, recognised that 8 hours is still the normal number of hours of work that a worker can work. Any hours more need to be compensated at a higher rate of wage.

What all these states removed with the amendment is the choice that workers enjoyed to refuse overtime. Overtime, according to law, had to be voluntary. If not voluntary, it would be considered to be forced labour and hence in violation of Article 23 of the Constitution. Thus whether it is a overtime rate paid extension of working hour or not, the violation of Article 23 holds.

- Night work for women

Section 66 of the Factories act disallowed factories from employing women between 7 pm and 6 am. This provision to protect women workers has been used against them both at the time of hiring and while at work by employers. The low presence of women in formal employments has many reasons, with this being one. Many states like Karnataka had removed this provision last year and in this round, Haryana has allowed factories to employ women in the night shift.

As per the last report published by the National Crime Record Bureau, Haryana has the highest rate of gang rapes in India. At 1.5%, this rate is five times higher than the national average of 0.3%. A total of 191 such cases were reported in Haryana, which means at least one such rape occurs every two days. In 2019, the Haryana Human Rights Commission took suo motu cognizance of a media report calling Haryana the ‘rape capital’ of India and sought a detailed report from the Director General of Police on measures taken by the police department to curb the rape cases and ensure safety of women. Despite the situation not changing drastically, the government of Haryana decided to allow employers now to hire women in night shifts.

- Fixed Term Contract Employment

The states of Goa, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar and Karnataka have amended their Standing Orders Act to allow FTCs in all establishments.

FTCs are used to replace permanent workers, in permanent jobs as a mean to bypass protection of workers under labour laws. It is used to break unions. It is used as a threat to create an atmosphere of fear among the most vulnerable workers, especially migrant workers, women workers. The introduction of FTCs in all establishments mean:

- Any employer can now hire as many workers under the FTC (upto 100% of the workforce) with no restriction on the nature of employment, whether perennial or not.

- The expiry of a FTC does not constitute termination by the employer. It is a termination by operation of law. Hence the employer can no longer be held responsible for the termination of a worker. Thus a worker can be hired and fired at will.

- Employers can keep employing these workers continuously working at an establishment as long as they wish, by renewing their contracts. No worker will be able to seek regularization after working for 240 days in the same establishment as under the Contract Labour Act.

- Wages and benefits of the workers under FTC can be kept at the entry level indefinitely as workers will not be able to claim experience at work.

- Workers under FTC do not enjoy the right to appeal against their termination, which is in violation of the basic principle of natural justice.

Introduction of the FTC is often justified by governments in the global south, including our own, that FTCs are being used across the world. It is a necessity of the time. However, unlike in India, the EU Council Directive requires governments to put in place one or more of the following limits for hiring of workers under FTCs: (i) requiring objective reasons for renewal; (ii) setting a maximum total duration of renewals; (iii) setting a permitted number of renewals. These limitations are put in place to ensure a framework of regulation even for workers hired under FTCs.

- Amendments Reducing Punitive action against Employers

Amendments that change working conditions, amendments that make laws inapplicable are not the only amendments that the states have made. To protect employers further, states such as Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh and Haryana have come up with a clause that creates a schedule of offences that employers can engage in and yet not be punished for it in the first violation. Haryana though is the only state that has listed this elaborate schedule of acts that an employer can engage which includes non-provisions of toilets, canteens, crèches, rest room, first aid, compensatory holiday, Non-maintenance of OT register, Non-maintenance of employment register; hours of work, and the denial of rights of workers. Thus this clause clearly allows employers to violate various rights of workers at work with permission.

This clause read together with the other amendment again in the state of Haryana that states that any offense by an employer will now be taken cognizance of only if it is made by an inspector sanctioned by the Chief Inspector. This takes away the right of a trade union or workers to file a complaint, without stating it in as many words.

These amendments are yet to be passed by other states but as the pattern for amendments show, there is a clear direction from the central government with standard clauses for change. This has been even revealed by the Gazette Notification of amendment by the Government of Tripura, that clearly stated that the amendment has been made under direction from the central Ministry of Labour and Employment. Thus change in one or more state could be indicative of what other states would come up with eventually.

Shall we Swim or Sink?

Will this ever increasing insecurity push workers towards collectivisation to build united strength to confront the consolidating power of employers in collusion with government? This will critically depend on bridging the gap between the ‘have not’s and the ‘have’s within the working class, i.e. those workers not covered by the laws at all and those small number of remaining workers who will technically remain covered by these laws. The ‘have not’s will have strength in number but will understandably be more insecure, while the ‘have’s will have resources, years of experience of collective bargaining, secured employment contracts but not numbers to confront employers. If each of these sections believes they will be able to protect their interest better by holding on to their forts and mistrusting the other section, we will all sink together. This division and mistrust between sections of workers is what management gurus base their models of control over workers on which allows employers to gain more and more control over workers. It is only by defeating these models of control shall we be able to swim together and ensure better conditions of work for all, and not just a small section of workers.