In presenting the Code on Social Security in parliament, the Labour Minister, Mr. Santosh Gangwar, stressed: “After 70 years of Independence, 50 crore workers, including the unorganised sector, will be brought into some kind of social security net. … We have taken ESIC to those in unorganised sector too. Those engaged in hazardous work have to mandatorily give ESIC. It will also be given to labour of tea estates. We have provided for a social security fund. This will help 40 crore labour in unorganised sector”

The social security code for the first time in Indian labour law legalised the division of workers into two distinct categories by definition: (i) Organised workers and (ii) Unorganised Workers, where an “unorganised worker” means a home-based worker, self-employed worker or a wage worker in the unorganised sector and includes a worker in the organised sector who is not covered by the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947 or Chapters III to VII of this Code. Notwithstanding the fact that the ID Act, 1947 has been subsumed in the IR Code, the definition specifically states that unorganised workers are those workers who are not covered under Chapter III (Employees Provident Fund), IV (Employees State Insurance Corporation), V (Gratuity), VI (Maternity Benefit) and VII (Employees Compensation). The definition itself is contradictory, as home-based workers or self-employed workers working as out-workers, as well as wage worker in any sector is defined to be a ‘workman’ under the ID Act, 1947 and hence should be classified as an ‘organised worker’ under this definition. Further, home-based workers such as Beedi workers are covered under EPF, construction workers are covered under EPF, employees’ compensation laws. Thus this definition is at best contradictory, and at worst, sows the seed of division between workers in different employments, thereby pitching one section of workers against another. Given this definition, workers will now have to prove at every step whether they are organised workers or unorganised ones. Under the existing laws, if a group of workers could prove that they are ‘workmen’ as defined under the ID Act, they were entitled to all labour rights. But under the code, a worker will first have to prove they are workers as defined under the IR Code, and then prove that they are organised workers to access legally protected labour rights.

If a worker is able to prove that they are organised workers, they shall be entitled to the legally protected rights under Chapter III to VII of the Social security code. The provisions under these chapters remain mostly unaltered, except for penalties. Workers could initiate a criminal case with the police for non-payment of PF against their employer under the existing law. This acted as a stringent deterrent for most employers. For non-compliance of all other social security rights, employers were liable to pay fines and/or with varying periods of jail term. The social security code, as in all other codes, allows employers an opportunity to correct their ‘mistake’ in the first instance of offense, making it easier for employers to violate laws with impunity. The fines for repeated offense within 3 years, have been increased from the existing fines but is definitely not commensurate to the rate of inflation in this period.

However, if a worker is fails to be recognised as an organised worker, the worker will have to self-register on an online portal and update it regularly to receive the benefits under the government social security schemes. Benefits under Schemes are not legally guaranteed – they are dependent on how these schemes are financed and the criteria set by the government to access these. In principle, this violates the constitutional right to equality before law (Article 14). The Code itself declares unorganised workers as unequal to organised workers with respect to rights they enjoy.

The Social Security Schemes will be financed through a Social Security Fund. The National social security fund was constituted in the year 2011 with an initial budget allocation of Rs 1,000 crore. During the UPA years 2010-11 to 2014-15, government announced budgetary support for the corpus. In their first budget in 2015, the NDA government allocated Rs. 607 crores to the fund but utilised nothing. Since then the government has not made any budgetary allocation for the NSSF. Instead the unused corpus was returned to the Consolidated Fund of India for other use, leaving the NSSF bag empty.

The Social Security Code re-introduces the social security fund for unorganised workers to be financed by central government, or a combination of centre and state governments, or a combination of centre and state governments and contributions from employers or beneficiaries, and finally also through other sources such as Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) funds.

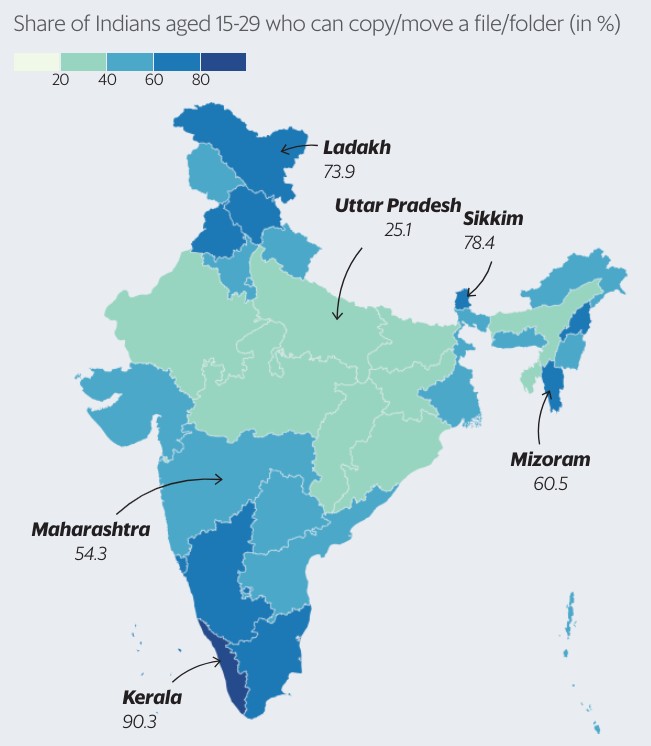

However, the onus of registering under these schemes and regularly updating their personal data online lies on the unorganised worker. With digital literacy being seriously challenged, by illiteracy, limited access to internet, limited connectivity in most parts of the country, the registration and regular updating of information to access the schemes will be a challenge for most workers.

Leave a Reply